They Crossed an Ocean Bigger Than the Moon

Let’s just start here: The Pacific Ocean is bigger than the surface area of the Moon. And the Polynesians, with no maps, no compasses, no GPS, no steel, managed to explore, settle, and thrive across it.

That’s not a metaphor. That’s not myth. They actually did it.

And the crazy part? Most people still have no idea how.

They Made the Pacific a Neighborhood

We like to think space travel is the peak of exploration, but hear me out: the Polynesians were doing something just as wild. They took double-hulled canoes the size of trucks and launched themselves into the unknown.

We’re talking about a culture that spread from New Zealand to Hawai’i to Easter Island. That’s like sailing from Norway to the tip of Africa, and then throwing in a detour to Argentina for fun.

No metal. No written language. Just deep, inherited knowledge. A kind of ocean literacy that feels almost mythical today.

Think about the sheer scale for a moment. From Hawai’i to New Zealand is over 4,000 miles of open ocean. That’s roughly the distance from New York to London. Easter Island sits 2,300 miles from the nearest major landmass. These weren’t short hops between visible islands. These were deliberate expeditions into the absolute void, betting everything on the belief that land existed somewhere out there.

And they made these journeys not once, but repeatedly. They didn’t just stumble onto islands by accident. They found them, settled them, and then sailed back and forth, maintaining contact across thousands of miles of ocean. They created a network of trade, culture, and kinship across the largest ocean on Earth.

How Do You Navigate Without Tools?

Imagine standing on the deck of a canoe made from trees you chopped down yourself. No engine. No satellite to ping your location. Just the wind, the waves, and a whole lot of guts.

Now imagine sailing that thing thousands of miles across open ocean, not just once, but over and over again, for generations.

The Polynesians developed a sophisticated system of navigation called wayfinding. It’s so complex that Western scientists are still trying to fully understand it. Master navigators, called wayfinders, spent decades learning to read the ocean like we read books.

Stars were their primary compass. Navigators memorized the rising and setting points of hundreds of stars throughout the year. They knew which stars passed directly overhead at different latitudes. They could determine their position based on star patterns even when clouds obscured parts of the sky. This wasn’t casual stargazing. This was astronomy as a survival skill.

But stars only work at night and when skies are clear. So they learned to read waves. Not just big waves, but the subtle swells that move through the ocean in consistent patterns. Waves refract around islands, creating interference patterns that a trained navigator can detect from dozens of miles away. They could feel these patterns in the motion of the canoe, using their bodies as instruments to detect land long before it was visible.

They watched birds. Certain species fly out from land in the morning and return at night, always within a specific range. Follow the birds at dusk, and you’ll find land. They observed cloud formations, which behave differently over islands than over open ocean. They noted water color, which changes near shallow reefs. They tracked ocean temperatures and currents.

They even looked at bioluminescence. The way plankton glow differently in different water conditions could provide navigational clues. Everything in the ocean was data if you knew how to read it.

From Hawaii to New Zealand, from Rapa Nui (Easter Island) to tiny atolls barely above sea level, Polynesians turned one of the most dangerous places on Earth into a string of connected homes. And they did it before the Romans had figured out how to cross the English Channel without freaking out.

It wasn’t just travel. It was mastery.

So Who Were These People?

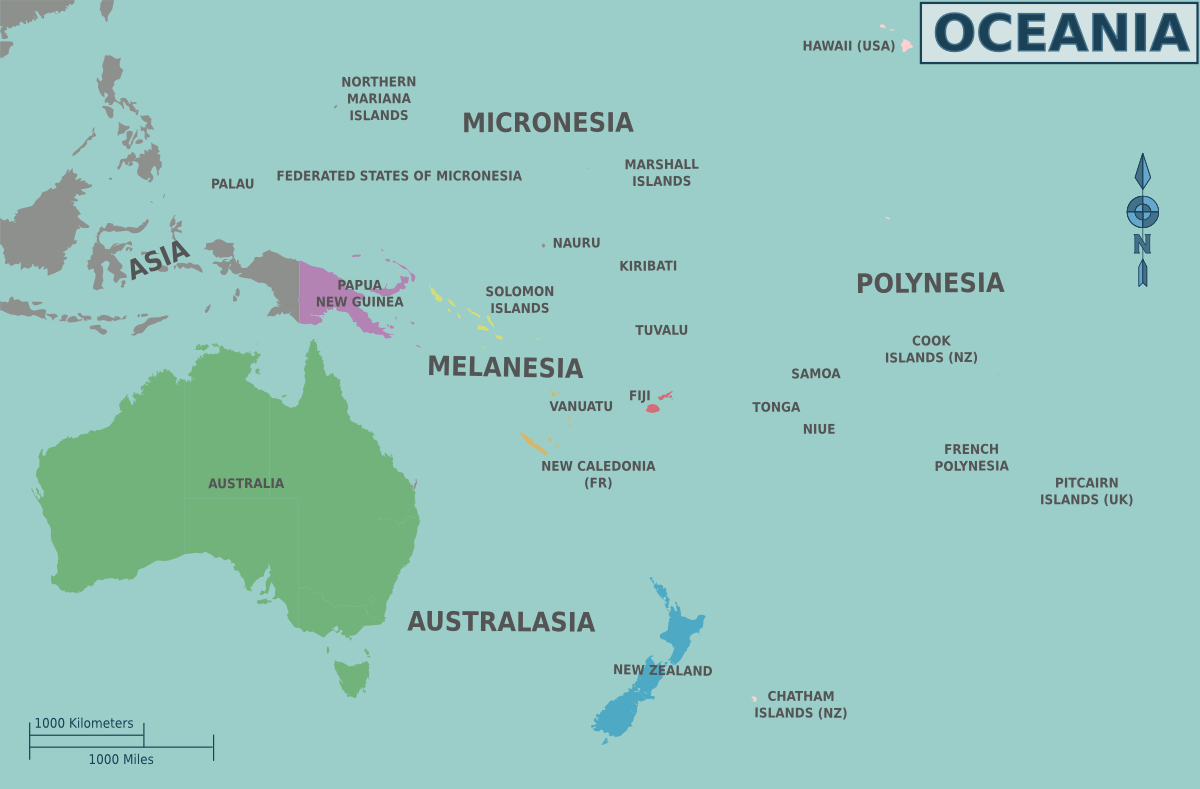

The word “Polynesian” covers a wide cultural and linguistic family that includes Hawaiians, Samoans, Tongans, Maoris, Tahitians, and more. But they all trace their roots to a remarkable group of seafaring people who began moving eastward from Taiwan and the Philippines around 3,000 years ago.

First they settled in Micronesia and Melanesia. Then, something shifted.

Somewhere around 1000 BCE, a small group pushed farther, beyond the visible islands, beyond the birds flying home at dusk, into what’s now called Remote Oceania. This wasn’t just a geographic move. It was a mental leap.

They went from island-hopping to straight-up ocean conquest.

Archaeological evidence shows they brought their entire agricultural package with them: taro, yams, breadfruit, coconuts, bananas, chickens, pigs, and dogs. They weren’t just exploring. They were colonizing, in the literal sense of establishing permanent settlements designed to be self-sufficient.

The Lapita culture, named after their distinctive pottery style, represents the earliest phase of this expansion. Their pottery shards have been found across thousands of miles of ocean, marking the path of their migrations. By around 900 CE, they had reached essentially every habitable island in the Pacific triangle, from New Zealand to Hawai’i to Easter Island.

That’s a span of nearly 2,000 years of continuous exploration and settlement. Multiple generations dedicating their lives to pushing further into the unknown. It’s one of the greatest sustained human migrations in history.

Their Boats? Basically Spacecraft on Water

Modern people tend to picture “canoe” and think of something you paddle down a calm river on a camping trip.

Nope.

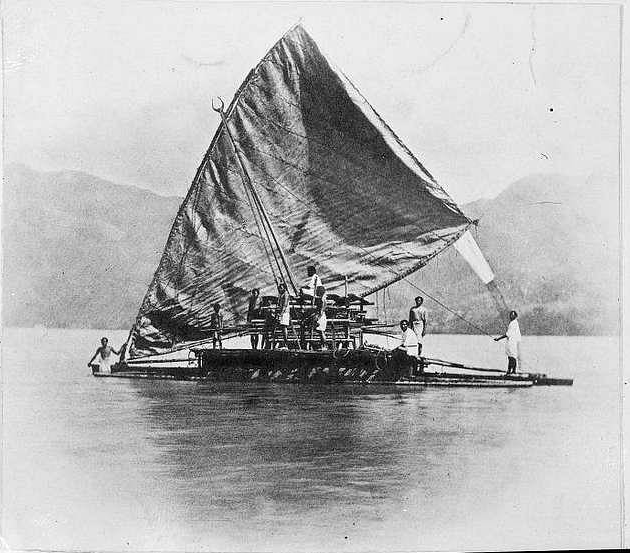

Polynesian voyaging canoes were sophisticated, double-hulled catamarans, some as long as 60 to 100 feet. Strong. Balanced. Fast. Capable of carrying families, food, animals, and the tools to start an entirely new life somewhere else.

They were the space shuttles of the sea, except built by hand from natural materials, with no blueprints, and entirely navigated by reading the environment.

The double-hull design was brilliant engineering. Two parallel hulls connected by a platform created exceptional stability in rough seas. Unlike single-hull boats that can capsize in strong winds, double-hulled canoes were nearly impossible to flip. The platform between the hulls provided space for cargo, shelter, and living quarters on long voyages.

The hulls were carved from massive trees, then expanded using carefully controlled heat and pressure. Planks were lashed together with coconut fiber rope following techniques that made the hull both strong and flexible, able to absorb the punishment of ocean waves without cracking. Every joint was sealed with breadfruit sap, creating a waterproof barrier.

The sails were woven from pandanus leaves, creating surprisingly efficient triangular or crab-claw shaped sails that could be adjusted for different wind conditions. These weren’t primitive blankets catching wind. They were carefully engineered airfoils that allowed the canoes to sail at angles to the wind, not just with it.

Speed estimates for these canoes range from 5 to 15 knots depending on conditions. That’s comparable to many sailing vessels used by European explorers centuries later. Some reconstructed voyaging canoes have logged 200+ miles in a single day.

It’s almost impossible to overstate how impressive that is. These boats were built to handle weeks at sea, not knowing when land might appear. And the people on them weren’t passengers. They were scientists. Artists. Astronomers. Philosophers. Survivors.

The Western World Didn’t Believe It

When European explorers first encountered Polynesian cultures spread across the Pacific, they couldn’t explain it. How did people without “advanced” technology end up on islands thousands of miles apart?

The prevailing theory, pushed by scholars for decades, was that Polynesians had drifted accidentally on currents and winds. They were portrayed as lucky castaways, not intentional navigators. Some theories even suggested they’d reached the islands from South America, not Southeast Asia, because Europeans couldn’t accept that people without metal or writing could accomplish such sophisticated navigation.

This racist dismissal of Polynesian achievement persisted well into the 20th century. Even when linguistic and genetic evidence clearly showed the Southeast Asian origins and deliberate settlement patterns, many Western academics clung to drift voyage theories.

Everything changed in 1976 when the Hōkūleʻa, a reconstructed traditional voyaging canoe, sailed from Hawai’i to Tahiti using only traditional wayfinding techniques. No instruments. No GPS. Just a master navigator named Mau Piailug from the Micronesian island of Satawal reading the ocean the way his ancestors had.

The 2,500-mile journey took 33 days and arrived within a few miles of the target island. It proved definitively that the ancient navigational techniques were not only real but remarkably accurate. Since then, the Hōkūleʻa has sailed over 150,000 miles using traditional navigation, visiting islands across the Pacific and beyond.

How Did They Know Where to Go?

Here’s one of the wildest parts: how did they know there were islands out there to find in the first place?

The answer involves a combination of observation, calculation, and courage. Polynesian navigators studied migratory patterns of birds. Some species travel enormous distances between breeding and feeding grounds, implying the existence of land beyond the horizon. Clouds that form over islands can be visible from far greater distances than the islands themselves. Shifts in wave patterns might indicate land upwind.

They also developed mental maps that were passed down through oral tradition. These weren’t just lists of islands. They were complex frameworks of relationships between stars, currents, wind patterns, and destinations. A navigator would memorize which star to follow, what wave patterns to expect, how many days the journey should take, and what signs indicated they were approaching land.

Some scholars believe they also made deliberate exploration voyages, sailing in specific directions for predetermined periods before turning back, gradually extending their knowledge of what lay in different directions. These expeditions would have been risky, but the potential reward of discovering new, uninhabited islands with fresh resources would have been enormous.

Once an island was found, the navigators had to be able to find it again. This required not just reaching the island but maintaining awareness of their route well enough to reverse it. The mental mapping involved is staggering. Modern cognitive scientists studying traditional navigation are amazed at the spatial reasoning and memory capabilities required.

What They Brought With Them

Every settlement voyage carried the seeds of civilization. Literally.

Canoes were loaded with agricultural starts: taro corms, yam tubers, breadfruit cuttings, coconuts for planting, banana shoots. They brought chickens in coops, pigs in pens, and dogs. They packed tools, fishing gear, clothing, and essential cultural items like carved gods and ceremonial objects.

They also brought water, stored in gourds and bamboo, and preserved food for the journey. Some voyages might last weeks. Everything needed for survival during the crossing and for establishing a new settlement had to fit on the canoe.

The agricultural package was crucial. Most Pacific islands lacked native food crops sufficient to support human populations. Without bringing their own food system, settlers would starve. The fact that they succeeded in transplanting entire agricultural systems to isolated islands, often with quite different climates than where the plants originated, demonstrates sophisticated understanding of horticulture.

They also brought their culture: languages, stories, songs, navigation techniques, building methods, social structures, and religious beliefs. Each new island became a variation on Polynesian culture, adapting to local conditions but maintaining connection to the broader cultural network.

The Environmental Cost

We should acknowledge that Polynesian settlement wasn’t without negative consequences. Many islands experienced significant environmental changes after human arrival.

Native bird species went extinct, particularly large flightless birds that had evolved without predators. Forests were cleared for agriculture. Easter Island’s famous deforestation, which contributed to the collapse of the island’s tree-carving moai culture, stands as perhaps the most dramatic example of unsustainable resource use.

Introduced species like rats (which arrived as stowaways on canoes) and pigs disrupted native ecosystems. Some islands experienced soil erosion after forests were cleared. The ecological impacts of Polynesian colonization remind us that even societies with deep environmental knowledge can make mistakes or face unintended consequences.

However, many Polynesian cultures also developed sustainable practices that allowed them to thrive for centuries on small islands with limited resources. The ahupua’a system in Hawai’i, which managed resources from mountain to sea as integrated units, represents sophisticated environmental management. The ra’ui system in parts of French Polynesia created temporary resource closures to allow recovery of overharvested species.

The Real Payoff: What This Means for Us

Why does this story matter?

Because it changes the way we see human history.

The Polynesians weren’t lucky castaways. They weren’t passive victims of their environment. They were engineers, explorers, and artists who solved one of the hardest problems on the planet: how to thrive in a water world.

They built societies on remote rocks in the middle of nowhere. They brought pigs, chickens, bananas, and breadfruit. They sang songs across waves and carved memories into stone. They taught their kids to watch the stars like they were old friends.

And they did all of this with nothing but knowledge, courage, and a stubborn belief that there was always something new out there, just beyond the horizon.

Their story challenges the idea that technological sophistication equals intelligence or capability. The Polynesians didn’t have metal or writing, but they accomplished feats of navigation that Europeans with compasses and charts couldn’t match for centuries. They prove that different cultures develop different forms of expertise, and that “primitive” is often just a failure of imagination on the part of the observer.

Their navigational knowledge also offers lessons for our current moment. In an age of GPS dependency, where many people can’t navigate their own cities without digital assistance, the Polynesian wayfinders remind us that deep environmental awareness and embodied knowledge have value. Their system of navigation was sustainable, requiring no external resources or technologies. It was resilient, working even when individual tools or techniques failed. And it was transmissible, passed down through apprenticeship and practice.

Modern voyaging societies are working to revive these traditional practices. Organizations like the Polynesian Voyaging Society in Hawai’i train new generations in wayfinding, not just as cultural preservation but as a way of reconnecting with ancestral knowledge and environmental wisdom.

The Greatest Long-Distance Voyage in Human History

When we talk about great human achievements, we mention pyramids, moon landings, and medical breakthroughs. We should talk more about the Polynesian expansion.

Over 2,000 years, they settled an area encompassing 10 million square miles, most of it empty ocean. They navigated with precision across distances that European sailors wouldn’t attempt for centuries. They adapted to environments ranging from tropical atolls to temperate New Zealand. They maintained cultural connections across vast distances without any form of long-distance communication technology.

And they did it in boats they built by hand, navigating by techniques they developed through observation and passed down through oral tradition, sustained by a vision of the ocean not as a barrier but as a highway.

That’s not just impressive. That’s world-historical. That’s humanity at its most curious, most courageous, most creative.

Final Thought: Looking Beyond the Horizon

The Polynesians teach us that the edge of the known world is an invitation, not a boundary. That careful observation and inherited wisdom can accomplish things technology alone cannot. That communities working together across generations can achieve the seemingly impossible.

When the first Polynesian canoe pushed beyond sight of land into the open Pacific, the navigators had no guarantee of finding anything. They went anyway. And they kept going, generation after generation, until they’d explored an ocean larger than the Moon’s surface.

We talk about exploring space, about sending missions to Mars, about the courage required to voyage into the unknown. The Polynesians already did that. They had their own space race, their own impossible frontier, their own leap into the void.

And they won.

So the next time you look at a map of the Pacific and see those tiny dots scattered across endless blue, remember: every single one represents someone who stood on a boat, looked at the stars, felt the waves, and decided that the horizon was worth sailing toward.

That’s the most human thing imaginable. And it’s absolutely extraordinary.

Sources:

1. Polynesian Voyaging Society https://hokulea.com/

2. BBC – The Genius of Polynesian Navigation

3. Smithsonian Magazine – Rediscovering Polynesian Navigation