Imagine this: You’re at a smoky piano bar in Washington, D.C., sipping your drink, when a violinist takes the stage. His performance is captivating, the music hauntingly beautiful. Unbeknownted to you, the instrument he’s playing is a stolen 1713 Stradivarius, missing for decades and worth millions.

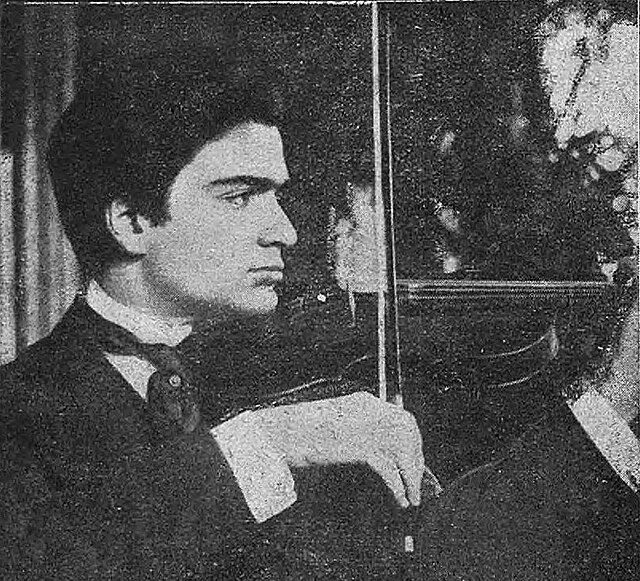

This isn’t a plot from a crime novel. It’s the true story of Julian Altman, a café musician who, in 1936, came into possession of the “Gibson” Stradivarius, stolen from virtuoso Bronisław Huberman’s dressing room at Carnegie Hall.

The Theft at Carnegie Hall

On February 28, 1936, Huberman was performing at Carnegie Hall. He had two prized violins: the 1713 Stradivarius and a 1731 Guarnerius. That night, due to the humidity, he chose to play the Guarnerius, leaving the Stradivarius in his dressing room. During the performance, the Stradivarius vanished.

The theft was discovered almost immediately after the concert ended. Huberman was devastated. This wasn’t just any violin. It was an instrument crafted by Antonio Stradivari during what experts consider his “golden period,” when he was producing the finest violins the world has ever known. The sound quality was extraordinary, irreplaceable. Insurance could cover the monetary value, but no amount of money could recreate what that specific instrument could do in the hands of a master.

The police investigation went nowhere. There were no witnesses, no leads, no fingerprints. Carnegie Hall had hundreds of people moving through it that night: musicians, stagehands, audience members, janitors. Any one of them could have slipped into the dressing room during those crucial minutes when Huberman was on stage.

Altman, a familiar face at Carnegie Hall and a performer at the nearby Russian Bear café, was never suspected. Some accounts suggest he stole the violin himself, slipping into the dressing room during the performance with the confidence of someone who belonged there. Others claim he bought it from a friend for $100, not initially knowing what he had. Regardless, Altman took measures to disguise the instrument, using shoe polish to alter its appearance and filing down the label inside.

Why Stradivarius Violins Matter

To understand the magnitude of this theft, you need to understand what a Stradivarius actually is. Between 1680 and 1720, Antonio Stradivari created approximately 1,100 instruments in his workshop in Cremona, Italy. Only about 650 survive today. Each one is unique, and the greatest violinists in history have fought over access to them.

The secret of their sound has never been fully replicated. Scientists have studied the wood, the varnish, the craftsmanship. Theories range from the density of wood from trees grown during the Little Ice Age to the specific chemical composition of Stradivari’s varnish. No one knows for sure. What we do know is that when played by a skilled musician, these instruments produce a sound that modern violins simply cannot match.

The Gibson Strad, as it came to be known, was particularly special. It had belonged to George Alfred Gibson, a wealthy amateur violinist, before Huberman acquired it. Its tone was warm and powerful, perfect for the concert halls Huberman performed in across Europe and America.

A Life Lived with a Stolen Masterpiece

For nearly five decades, Altman played the stolen Stradivarius in various venues, from bars to performances for U.S. presidents. He even held a position with the National Symphony Orchestra during World War II. Despite the instrument’s value and uniqueness, no one identified it as the missing Stradivarius.

This is the part that’s hardest to believe. Altman wasn’t hiding in a basement somewhere. He was out there, performing publicly, with what should have been one of the most recognizable instruments on Earth. But remember, he’d disguised it. The shoe polish darkened the wood. He’d tampered with the label. And most importantly, who would suspect a café musician of possessing a million-dollar violin?

People saw what they expected to see: a working musician with his instrument. The context told the story for him. If you’re playing in dive bars and small venues for tips, obviously you don’t have a priceless Stradivarius. That would be crazy. Except it wasn’t crazy. It was happening.

Altman’s performances were reportedly good, sometimes very good, but he never achieved the fame of someone like Huberman. He lived a modest life, moving from gig to gig, never drawing too much attention. The violin that should have been his ticket to wealth and recognition became instead his secret, something he couldn’t fully capitalize on without exposing himself.

The irony is thick. He possessed one of the finest instruments ever made but had to hide that fact to avoid getting caught. He could play it, feel its responsiveness, hear its perfect tone, but he could never really claim it. Never tell anyone what he had. Never get it properly maintained by experts who would immediately recognize it.

The Deathbed Confession

In 1985, while serving a prison sentence for unrelated crimes, Altman was diagnosed with terminal cancer. On his deathbed, he confessed to his wife, Marcelle Hall, about the violin’s true identity. He directed her to hidden newspaper clippings detailing the 1936 theft, carefully preserved for nearly fifty years.

Hall was reportedly shocked. She’d known her husband was a musician, knew he cherished that violin, but had no idea of its history. Altman told her everything in those final days. The theft, or the purchase from a thief, the decades of performances, the constant fear of discovery. The guilt he’d carried all those years.

Following his death, Hall faced a choice. She could keep the violin, try to sell it on the black market, continue the deception. Or she could do the right thing. She chose honesty.

Hall returned the violin to Lloyd’s of London, the insurer that had compensated Huberman back in 1936. She received a finder’s fee of $263,000, a fraction of the violin’s value but still a substantial sum. More importantly, she freed herself from the burden her husband had carried for half a century.

Restoration and Rebirth

The instrument underwent a nine-month restoration. Experts carefully removed Altman’s crude attempts at disguise, revealing the original varnish beneath the shoe polish. They repaired decades of wear and inadequate maintenance. The violin had survived, but it needed serious work to return to concert-ready condition.

The restoration was delicate work. Stradivarius violins require specialists who understand not just violin construction but the specific quirks of these historic instruments. One wrong move, too much pressure in the wrong spot, and you could destroy something irreplaceable.

When the work was complete, the Gibson Strad was sold to British violinist Norbert Brainin for $1.2 million. Brainin, founder of the legendary Amadeus Quartet, finally gave the instrument the platform it deserved. For the first time in fifty years, the violin was being played at the highest levels of performance, in concert halls around the world, by a musician who could fully utilize its capabilities.

A New Chapter with Joshua Bell

In 2001, renowned American violinist Joshua Bell acquired the restored Stradivarius for nearly $4 million. He has since performed and recorded extensively with the instrument, now known as the Gibson ex-Huberman. Bell has taken it to venues around the world, from Carnegie Hall (where it was stolen) to small subway stations (in a famous 2007 experiment where he played incognito and most commuters ignored him).

Bell treats the violin with the reverence it deserves while also challenging the pretensions around classical music. He’s played pop songs on it. He’s used it in crossover projects. He’s made the instrument accessible to new audiences who might never attend a traditional classical concert.

The violin’s journey from Stradivari’s workshop in 1713 to Bell’s hands in 2025 spans three centuries, two world wars, one brazen theft, and countless performances. It survived Nazi Germany (Huberman fled Europe before the Holocaust), fifty years in hiding, and restoration after decades of neglect.

What Happened to Huberman?

Bronisław Huberman never got his violin back. He died in 1947, still mourning the loss. But his legacy extends beyond the stolen Strad. In 1936, the same year his violin was stolen, Huberman founded the Palestine Philharmonic Orchestra (now the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra), rescuing dozens of Jewish musicians from Nazi-occupied Europe in the process.

He saved lives while losing his most prized possession. The violin eventually returned to the concert stage. Huberman’s rescued musicians and their descendants continue performing today. Both legacies endure.

A Tale of Music, Mystery, and Redemption

The story of Julian Altman and the stolen Stradivarius is a compelling narrative of crime, concealment, and the enduring power of music. It’s a reminder that even the most extraordinary treasures can be hidden in plain sight, waiting for their stories to be uncovered.

It also raises questions about art, ownership, and legacy. Did those fifty years in Altman’s hands diminish the violin’s value, or did his performances, however modest, keep it alive and resonating? Can a stolen instrument still serve beauty? Can music transcend the circumstances of its creation?

The Gibson ex-Huberman has its answer. It keeps playing, keeps singing, keeps drawing audiences into its remarkable sound. The theft is part of its story now, not a stain to be removed but a chapter that makes the whole narrative richer.

And somewhere, maybe Huberman and Altman have made their peace. One man who lost everything but saved hundreds. Another who stole something priceless but gave it voice for half a century. Both loved the same violin. Both understood what it could do.

The music continues.

Sources:

1. The thief, his wife and the ‘Huberman’ Strad https://www.thestrad.com/lutherie/the-thief-his-wife-and-the-huberman-strad/8627.article

2. Secret of Stolen Masterpiece Revealed : ‘$100 Fiddle’ an $800,000 Stradivarius https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1987-05-14-mn-9193-story.html

3. Violin at center of court fight, 60 years after theft https://www.tampabay.com/archive/1996/11/15/violin-at-center-of-court-fight-60-years-after-theft/