You probably think of them as silent sword-wielders with topknots and stoic stares. Maybe a cherry blossom drifts by while they decapitate a foe with a whisper of steel. The camera lingers on their unreadable face. Cue dramatic music. Roll credits.

But the real samurai? Far stranger, smarter, and more layered than Hollywood ever gave them credit for.

Not Just Warriors

Samurai weren’t born with katanas in their cribs. For centuries, they were administrators, poets, and government nerds. The word “samurai” means “to serve,” and serve they did, not just on the battlefield but in tax offices, rice storehouses, and diplomatic missions.

They were bureaucrats as much as warriors. During the Edo period (1603-1868), Japan experienced over 250 years of relative peace. That’s a lot of downtime for a warrior class. So what did samurai do? They managed provinces, collected taxes, adjudicated disputes, and kept meticulous records. Some of them probably spent more time with ink brushes than swords.

Think of it like if your local DMV clerk also trained in lethal swordplay just in case things got wild in the parking lot. Except the stakes were higher, the paperwork was written with a brush on rice paper, and failing at your administrative duties could result in your entire family being dishonored.

Samurai were expected to be educated. They studied Confucian philosophy, calligraphy, poetry, and tea ceremony. A truly accomplished samurai could compose a haiku about the fleeting nature of existence, arrange flowers to reflect the seasons, and then efficiently run the tax collection system for an entire province.

This wasn’t optional. It was part of being samurai. You weren’t considered truly refined if all you could do was swing a sword. That was base, almost barbaric. Real status came from mastering both the martial and cultural arts, a concept called bunbu-ryodo, the dual way of pen and sword.

The Myth of the Katana

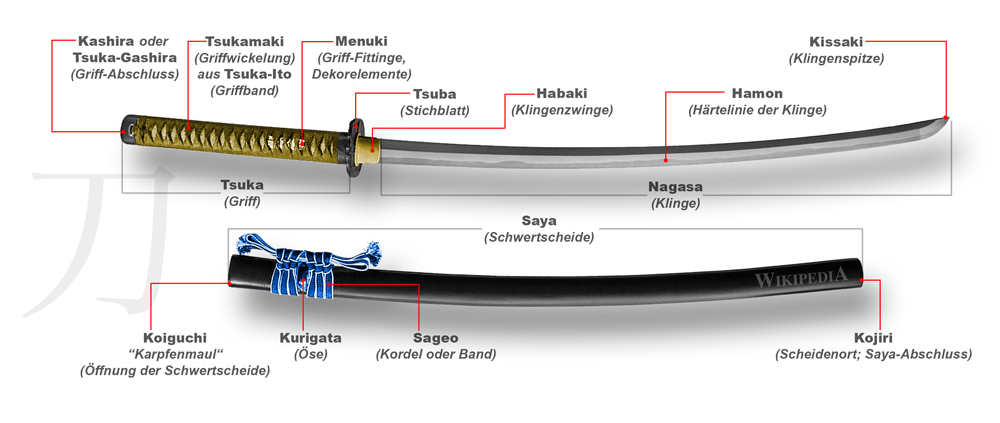

Let’s talk about the sword. The katana is legendary. Beautiful, yes. Deadly, sure. The curved blade, the distinctive edge, the way it cuts through bamboo in demonstration videos, all very impressive.

But it wasn’t always the weapon of choice. Early samurai, from roughly the 10th to 14th centuries, often used bows as their primary weapon. Archery was their main jam. A samurai on horseback, raining arrows with terrifying precision, that was peak battlefield style for a long time. The yumi, or Japanese longbow, was enormous, sometimes over two meters tall, and required years of training to master.

In fact, the first samurai would have been confused if you called them swordsmen. They were horse archers first, everything else second. Battles were won by cavalry units shooting from a distance, not by dramatic one-on-one sword duels.

Swords came later, as warfare evolved and close combat became more common during the chaotic Sengoku period (1467-1615), the age of warring states. And even then, on actual battlefields, samurai often used spears (yari) or polearms because they had better reach and were more practical in formation fighting.

The katana? It became more status symbol than battlefield necessity, especially during the long peacetime of the Edo period when you were less likely to need to chop anyone in half. A polished katana tucked into your sash said, “I have discipline, training, and the means to kill you if needed. But also, I read poetry and understand the philosophical implications of cherry blossoms.”

The swords themselves were works of art. Master swordsmiths spent months forging a single blade, folding the steel repeatedly to remove impurities and create that distinctive wavy pattern in the metal. Owning a blade from a famous smith was like owning a Picasso. You might never use it, but having it announced your taste and wealth.

Code of Honor or Just Good PR?

You’ve probably heard of bushido, the so-called “way of the warrior.” Loyalty. Courage. Honor. Self-sacrifice. A lot of it sounds noble. Almost too noble. That’s because much of what we think of as bushido was written down long after the actual samurai age was in decline, sometimes centuries later.

During the Edo period, when Japan was relatively peaceful and samurai spent more time governing than fighting, they needed something to justify their continued existence and privileged status. Why should they get stipends of rice and maintain their social position if there were no wars to fight?

Cue romanticized codes and dramatic stories. Books like “Hagakure,” written in the early 1700s, codified bushido principles, but they were as much about nostalgia and maintaining social hierarchy as about actual historical practice. It’s like if someone in 2025 wrote a book about “the true cowboy code” based on old Western movies rather than actual frontier life.

Were some samurai incredibly loyal? Sure. The famous 47 Ronin story celebrates samurai who avenged their master’s death, then committed ritual suicide. It’s a cornerstone of bushido mythology. Others? Known to swap sides if the coin was shinier or survival looked better on the other team. Like any social class across history, they were a mixed bag of idealists, opportunists, cowards, and heroes.

The reality is that samurai were people, and people are complicated. Some lived up to the ideals. Others ignored them completely. And the ideals themselves shifted depending on the era, the region, and who was doing the writing.

Strange Habits, Stranger Laws

Some of the stuff samurai lived by feels almost absurd today. For instance, there was a rule against drawing your sword in public unless you meant to kill. If you did draw it, you had to shed blood. Otherwise, you’d dishonor yourself. This wasn’t just custom. It was law during certain periods.

So imagine accidentally drawing your katana because you tripped or because someone bumped into you in a crowded market. Now you’re legally obligated to kill something or someone. Some samurai would reportedly cut down a dog or a peasant (yes, really) rather than face the shame of sheathing a drawn but unused blade. This practice, called tsujigiri or “crossroads killing,” was eventually banned but the stories persisted.

There were also strict rules on dress, speech, and behavior. Social standing was visible in everything from the tilt of your hat to how you tied your sandals. One wrong move and you risked shame, or worse, forced suicide called seppuku, which was somehow both punishment and honor.

Seppuku itself was ritualized in ways that seem theatrical but were deadly serious. You’d disembowel yourself with a short blade while a designated assistant stood by to decapitate you at the right moment, sparing you prolonged agony. Failing to perform seppuku correctly brought shame to your entire family.

Sources:

1. History.com – Samurai and Bushido

2. Nippon – Japan Topics

3. Britannica – Samurai

4. Tofugu – Female Samurai