Picture this: You’re a child in rural China, 8 years old. One day, your father tells you you’re going to become a servant in the Forbidden City. It sounds grand until you learn what it really means. No school. No play. No future family. And one more thing: you’re getting castrated.

That was Sun Yaoting’s childhood. He wasn’t born into privilege or chosen by fate. He was born into crushing poverty in a dying dynasty, and his life would become one of the strangest, most tragic, and most fascinating windows into China’s imperial past.

This is the story of a boy who gave up everything for a world that was already disappearing, and lived long enough to see just how much he’d lost.

A Father’s Desperate Gamble

Sun Yaoting was born in 1902 in Jinghai County, a poor rural area near Tianjin in northern China. His family was dirt poor, the kind of poverty where every harvest meant the difference between eating and starving. His father worked as a farmer, scraping by on a small plot of land that barely fed the family.

In those days, families had limited options for escaping poverty. You could hope for a good marriage, apprentice your son to a trade, or take a darker path that promised wealth and influence: make your son a eunuch.

For centuries, eunuchs had held real power in Chinese imperial courts. They served in the inner chambers of the palace, places where other men couldn’t go. They managed imperial finances, delivered messages between the emperor and his officials, and sometimes became trusted advisors to emperors and empresses. Some accumulated enormous wealth. A few even controlled entire governments from behind the throne.

But by the early 1900s, that golden age was long over. The Qing Dynasty was collapsing. Eunuchs had become symbols of corruption and decadence. Their power had been stripped away by reforms. Yet the myth persisted in poor villages that becoming a palace eunuch was still a path to riches.

Sun’s father believed that myth. Or maybe he was just that desperate. When Sun was only 8 years old, his father made the decision that would define his son’s entire life.

The Procedure That Changed Everything

The castration itself was brutal and often deadly. Families paid specialists called “knife operators” to perform the procedure. There was no anesthesia, just maybe some opium if you were lucky. The operation had to be done quickly, and infection was common. Many boys didn’t survive.

Sun did survive, but the physical and psychological trauma stayed with him forever. In interviews late in his life, he spoke about the pain, the fear, and the sense that his childhood had been stolen in a single afternoon. His father had made the choice. Sun had no say in it. He was 8 years old.

After the operation, there was a recovery period of several weeks. Then came years of waiting. Sun’s father kept the “proof” of the castration preserved in a jar, a requirement for entering palace service. But getting into the Forbidden City wasn’t automatic. You needed connections, bribes, and luck.

It took years before Sun finally received word that he could enter the palace. By then, he was a teenager. The Qing Dynasty had already fallen in 1911, though the imperial family still lived in the Forbidden City under an agreement with the new Republic of China. Sun’s father had castrated his son for a dynasty that no longer existed.

The Forbidden City’s Hidden Prison

In the waning years of the Qing Dynasty, the Forbidden City wasn’t just a palace. It was a cage of rituals, rules, and whispers. To survive there as a eunuch was to vanish into a life of silence and service, invisible labor that kept the imperial machinery running.

Sun Yaoting, who arrived as a teenager in 1916, quickly learned that he wasn’t just working for royalty. He was becoming a ghost in the machinery of empire, one of hundreds of eunuchs who lived in cramped quarters, followed strict hierarchies, and performed endless repetitive tasks.

And yet, he wanted it. Or at least, his father did. And by the time Sun arrived, there was no going back. He was already castrated. His only option was to make the best of the life that had been chosen for him.

The reality of palace life was nothing like the stories. Eunuchs were once powerful, controlling imperial secrets, finances, even emperors. But by the time Sun arrived, their power was a fading memory. The eunuchs who remained were mostly servants, and not even particularly respected ones. They cleaned, cooked, and ran errands for an imperial family that had no real empire to rule.

Life Behind the Red Walls

Daily life in the Forbidden City followed rigid patterns that hadn’t changed in centuries. Sun woke before dawn, performed purification rituals, and began his duties. He might spend hours preparing ceremonial robes, lighting incense at ancestral altars, or simply waiting in hallways in case someone needed something.

The palace was enormous, nearly 200 acres with over 900 buildings. But for eunuchs, movement was restricted. They couldn’t leave without permission. They couldn’t marry or have families. They lived in communal quarters, often several to a small room, with little privacy or personal space.

There was a strict hierarchy among eunuchs. Those who served the emperor or empress directly had status and received better treatment. Lower-ranking eunuchs like Sun did menial work and were frequently punished for small mistakes. Beatings were common. So was humiliation.

Sun later recalled that the palace felt like a beautiful prison. The architecture was magnificent, the gardens were stunning, but the people inside were trapped by tradition and circumstance. Everyone, from the emperor down to the lowest servant, was playing a role in a performance that no longer had an audience.

From Child to Servant of the Last Emperor

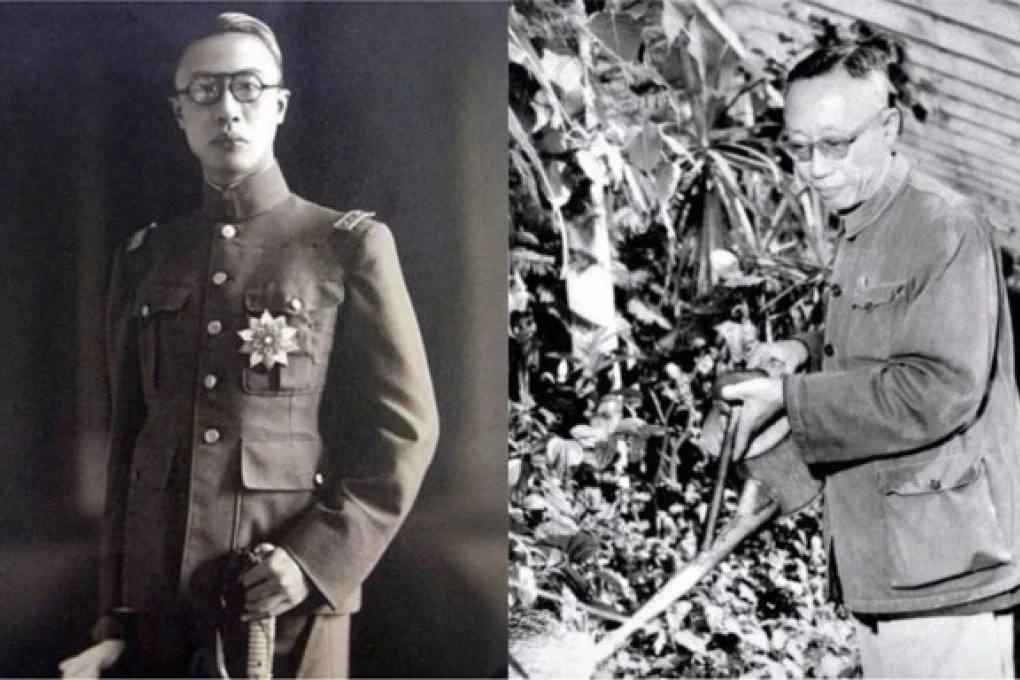

Sun Yaoting arrived at the palace in the final flicker of imperial China. He was personally crowned by Puyi, the last emperor. But Puyi wasn’t ruling anything. He was an awkward teenager himself, playing dress-up in a palace that no longer ruled anything, kept isolated from the real China transforming outside the palace walls.

Puyi had become emperor at age 2 in 1908. When the revolution came in 1911, he was only 5 years old. The revolutionaries allowed him to keep his title and continue living in the Forbidden City as part of a deal with the imperial family, but he had no actual power. He was essentially a living museum piece.

The empire had already fallen, but the emperor still lived in the Forbidden City like a ghost of the past. It was like watching someone act out a play after the curtain had already dropped, going through all the motions even though everyone knew it was just pretend.

And Sun? He was backstage. Fetching robes, lighting incense, watching the last act unfold. He served in the inner court, close enough to witness the strange, sad reality of the imperial family’s existence.

The Boy Emperor’s Lonely Kingdom

Sun later described Puyi as a lonely, confused young man who had been raised to believe he was divine but treated more like a prisoner. Puyi was educated by tutors who taught him about an empire that no longer existed. He was surrounded by servants but had no real friends. The palace, meant to be the center of the universe, had become a gilded cage.

The eunuchs witnessed Puyi’s frustrations, his tantrums, and his growing awareness that he was living a lie. Some felt sorry for him. Others resented having sacrificed so much to serve someone with no real power. Sun seems to have felt both.

When the Curtain Finally Fell

In 1924, everything changed. A warlord named Feng Yuxiang seized control of Beijing and decided the imperial family had outlived their usefulness. On November 5, 1924, the Chinese government expelled Puyi from the palace. Soldiers entered the Forbidden City and gave the emperor and his household just a few hours to leave.

With Puyi went the eunuchs. Just like that, Sun Yaoting lost everything he’d been castrated for. No pension. No farewell ceremony. No acknowledgment of their service or sacrifice. The gates closed behind them, and they were on their own in a China that had moved on.

For Sun, the expulsion was devastating. He was 22 years old, castrated, with no education or marketable skills. The only life he’d known was palace service, and that life was over. He wandered the streets of Beijing, shaved heads for pennies at barbershops, and lived in Buddhist temples that took pity on him.

No job. No family. No real identity. Just a man who had sacrificed everything for a world that no longer existed and wanted nothing to do with its remnants.

The Years of Wandering

The decades that followed were hard. Sun survived on odd jobs and charity. He reconnected with other former eunuchs, men who shared his strange fate. They formed a kind of community, supporting each other as best they could, though many fell into poverty, addiction, or despair.

Some former eunuchs tried to hide their past, but their high-pitched voices and lack of facial hair made them recognizable. They faced discrimination and mockery. In traditional Chinese culture, which prized family continuity and producing heirs, eunuchs were seen as incomplete, pitiful figures.

Sun worked various jobs over the years. He tended gardens, cleaned houses, and did whatever work he could find. He never married, obviously, and never had children. He lived quietly, trying not to draw attention to himself, especially as China went through massive upheavals.

A Living Relic in a Changing China

And yet, Sun lived on. For decades. Long after emperors were gone, after the rise of communism, the Cultural Revolution, and even the modernization of China. He was a relic walking through history, one of the last living threads to a vanished world.

During the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s and 70s, being associated with the old imperial system was dangerous. Sun kept his head down, avoided talking about his past, and survived by being invisible. Many others with connections to the old regime were persecuted, imprisoned, or killed. Sun somehow slipped through unnoticed.

As China began opening up in the 1980s, attitudes started to change. Historians became interested in preserving memories of the imperial era before everyone who had lived through it died. Sun Yaoting was one of the last people alive who had actually served in the Forbidden City during the final years of the dynasty.

Finally Breaking the Silence

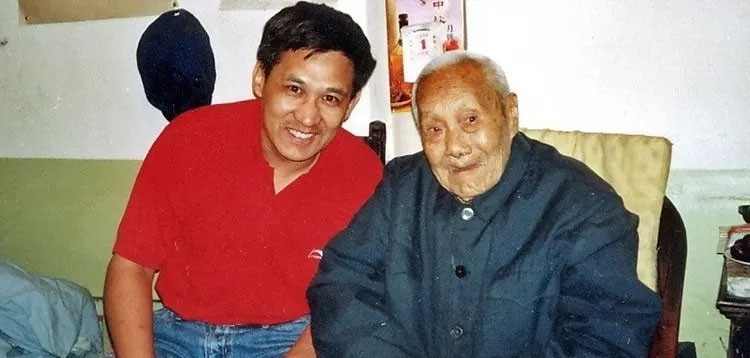

In his old age, Sun finally spoke. He told his story to a writer named Jia Yinghua, who spent years interviewing him and other former palace servants. And it became a book: “The Last Eunuch of China: The Life of Sun Yaoting.” Through Sun’s eyes, we saw a world that had been sealed off by walls, politics, and shame.

Sun was in his 80s and 90s when he gave these interviews. He spoke frankly about things Chinese society had long considered taboo: the castration, the loneliness, the sense of having been used and discarded. He didn’t glorify the imperial system. He described it honestly, with all its cruelty and absurdity.

His testimony was invaluable. Most records of palace life were written by scholars and officials, not by the servants who actually lived there. Sun provided details about daily routines, palace politics, and the human reality behind the ceremonies that no official history recorded.

He died in 1996 at the age of 94. Not just the last eunuch, but the last person alive who had served an emperor of China. With his death, a direct connection to thousands of years of imperial tradition was finally severed.

What We See Through Him

Sun Yaoting’s story isn’t just about strange old customs or exotic historical trivia. It’s about what people sacrifice for survival. About the pressure of tradition, family obligation, and grinding poverty that forces impossible choices.

It’s about how a child’s life can be shaped, or destroyed, by a parent’s desperation. Sun’s father thought he was giving his son an opportunity. In reality, he condemned him to a life of servitude, physical mutilation, and permanent exclusion from normal society. And he did it all for a system that collapsed before Sun even entered it.

But Sun’s story is also about resilience. He survived the operation, survived palace life, survived the collapse of everything he’d been prepared for, and somehow kept going through decades of poverty and irrelevance. He lived nearly a century, long enough to see his story go from shameful secret to historical treasure.

The Weight of Memory

But mostly, Sun’s story is about memory. He remembered a world we forgot, or never knew existed. The Qing Dynasty feels like ancient history, but Sun Yaoting was alive until 1996. He watched China transform from empire to republic to communist state to emerging superpower, all while carrying the mark of a system that had disappeared almost as soon as he entered it.

Because he told his story, because he broke the silence and shared his truth, we get to remember it too. We get to understand what imperial China actually felt like from the inside, not from historians and textbooks but from someone who lived it.

His life was a tragedy in many ways. But his willingness to speak, to preserve his memories for future generations, transformed that tragedy into something meaningful. He became a witness to history, a living bridge between China’s imperial past and its modern present.

And now, every time someone learns about Sun Yaoting, every time his story gets shared and discussed, a little bit of that lost world comes back to life. That’s not the immortality his father dreamed of when he made his terrible choice. But it’s a kind of immortality nonetheless.

Sun Yaoting’s life reminds us that history isn’t just dates and dynasties. It’s people. It’s children who had no choice in their fate. It’s ordinary individuals caught up in extraordinary times. And sometimes, if we’re lucky, those people survive long enough to tell us what it was really like.

That’s the gift Sun gave us. Not wisdom about how to live, but truth about how he lived, and why, and what it cost. In a world that wanted to forget the eunuchs, he made sure we’d remember.

Sources:

1. The Last Eunuch of China by Jia Yinghua

2. BBC: China’s Last Eunuch

3. China Heritage: The Eunuch of the Last Dynasty