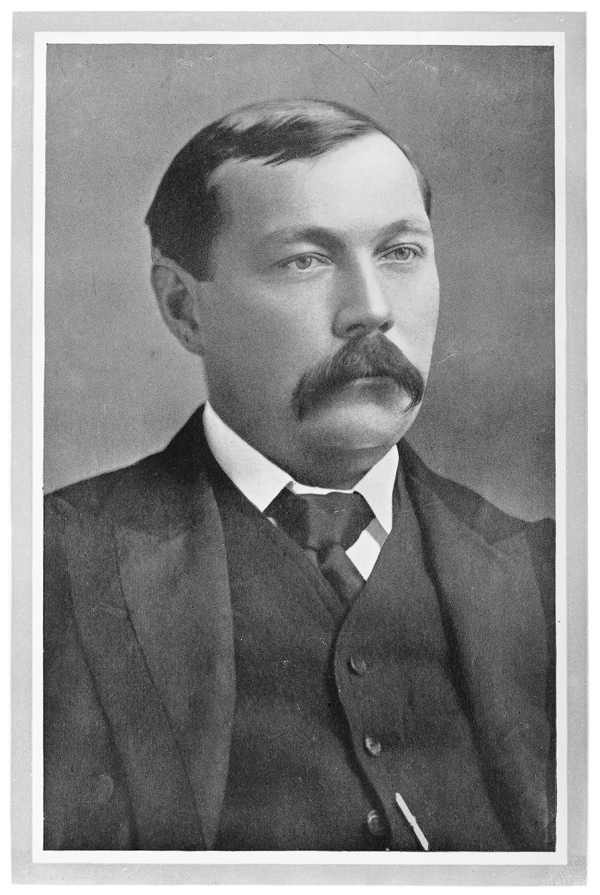

On December 1893, Arthur Conan Doyle killed the most famous detective in the world.

Sherlock Holmes died at the edge of a waterfall in Switzerland, locked in a death-grapple with Professor Moriarty. Readers were stunned. Some wept. Others wore black armbands in mourning. One newspaper is said to have declared: “We mourn Sherlock Holmes as we would a real person.”

But Holmes wasn’t real. Right?

The Murder of a Fictional Man

Here’s the thing. Doyle didn’t hate Holmes. Not exactly. But he resented him.

Holmes had made Doyle rich, yes. Famous, absolutely. But also stuck. The character overshadowed everything else he tried to write. Doyle wanted to be remembered as a serious historical novelist, a man of letters who tackled important themes. He’d written books like “The White Company” and “Micah Clarke,” historical epics he poured his heart into. He thought those would be his legacy.

Instead, people wanted more stories about the cocaine-using detective who solved crimes from his armchair.

So he pushed Holmes off a cliff. Literally. He wrote “The Final Problem” and sent Holmes tumbling into the Reichenbach Falls, locked in combat with the criminal mastermind Moriarty, a villain Doyle invented specifically for this purpose. Moriarty appeared in exactly one story before the death scene. He was a plot device designed to give Holmes a worthy end.

And Doyle thought that would be that. He wrote to his mother beforehand, telling her he was “thinking of slaying Holmes.” She begged him not to. He did it anyway.

Fans Lost Their Minds

They weren’t ready to let go. Letters poured in. Thousands of them. Some addressed to Doyle, others to Holmes himself at 221B Baker Street, begging him to return. One woman started her letter, “You brute.” Men stopped Doyle on the street to express their anger. The Strand Magazine, which published the Holmes stories, reportedly lost 20,000 subscribers overnight.

This was 1893. Social media didn’t exist. There were no fan forums or Reddit threads. But the Victorian public found ways to make their fury known. Young men in London wore black mourning bands on their arms. Businessmen reportedly canceled their subscriptions to The Strand in protest. The magazine’s editor, Herbert Greenhough Smith, pleaded with Doyle to reconsider.

Publishers panicked. Magazine sales dipped. The Strand had built its reputation partly on Holmes stories. Without them, the publication was just another periodical in a crowded market.

Doyle held firm for a while. He even got some satisfaction out of it. In letters to friends, he seemed almost gleeful about escaping Holmes’s shadow. He could finally focus on what he considered important work. He threw himself into historical fiction, into spiritualism (which became an obsession later in life), into political commentary.

But the pressure didn’t stop. It grew louder, more relentless, and more profitable. Publishers offered astronomical sums for new Holmes stories. The American market was particularly aggressive, dangling fees that would be equivalent to hundreds of thousands of dollars today for a single short story.

Life Without Holmes

For eight years, Doyle tried to live in a world without Sherlock Holmes. He wrote plays. He wrote more historical novels. He served as a physician during the Boer War and wrote accounts of the conflict. He even ran for Parliament twice (he lost both times).

Some of his work was genuinely good. His historical novels received respectable reviews. Critics praised his research and narrative skill. But they didn’t become cultural phenomena. They didn’t spawn imitators or obsessive fans. They were simply books, read and then forgotten.

Meanwhile, Holmes lived on without Doyle’s permission. Pirated stories appeared. Other writers tried to continue the series. Theatrical adaptations kept Holmes alive on stage. The character had taken on a life independent of his creator, which must have been both frustrating and fascinating for Doyle to witness.

Then Came the Resurrection

In 1901, Doyle published “The Hound of the Baskervilles.” It was a prequel, technically. Holmes was still dead. The story was set before the Reichenbach Falls incident. But the public smelled a comeback. Sales were massive. The Strand’s circulation jumped. People lined up outside newsstands on publication day.

Doyle saw those numbers. He saw the enthusiasm. And more importantly, he saw the money being offered for an actual return. The American publisher Collier’s Weekly offered Doyle $5,000 per story, an absolutely staggering sum at the time. In today’s money, that’s roughly $150,000 per story.

By 1903, Doyle gave in. “The Adventure of the Empty House” brought Holmes back from the grave. The explanation was almost hilariously simple: Holmes had faked his death to outwit Moriarty’s remaining henchmen. He’d been traveling in Asia under assumed names, only now returning to London.

Some fans bought it. Others didn’t care about the logic. Sherlock Holmes was alive again. That was enough. The story opens with Watson fainting when he realizes his dead friend is standing in his study. Victorian readers probably understood the feeling.

Why Did Doyle Really Do It?

The easy answer is money. And sure, Doyle was offered an absurd amount for new Holmes stories. But it wasn’t just that.

He’d tried to live without Holmes. He wrote historical novels, war commentaries, plays. Some were decent. None were Holmes. None captured the public imagination the way those detective stories did. And there’s a special kind of torment in that realization, that your best work, the thing you’ll be remembered for, is the thing you didn’t even value most highly.

People didn’t want Doyle the historian. They didn’t want Doyle the spiritualist or Doyle the war correspondent. They wanted the detective with the pipe, the violin, and the cold logic. They wanted Watson’s narration, the fog of London, the hansom cabs racing through gaslit streets.

Eventually, Doyle realized something every creator fears: your character might be smarter, stronger, and more beloved than you. Holmes had become bigger than Doyle. The creation had surpassed the creator.

There’s also a simpler possibility. Maybe Doyle actually missed writing Holmes. Maybe after eight years away, he remembered why he’d created the character in the first place. The puzzle-box structure of the stories. The interplay between Holmes and Watson. The satisfaction of constructing a perfect mystery and then unraveling it.

Holmes Outsmarted His Own Creator

After his return, Holmes stayed. Doyle kept writing him until 1927, producing 33 more stories after the resurrection. Even when he felt tired of the formula. Even when his heart wasn’t fully in it.

But something shifted. Later Holmes stories had more introspection. A little more weariness. Less sparkle, more soul. Holmes aged. He retired to keep bees in Sussex. He grew philosophical. In “His Last Bow,” set during World War I, Holmes comes out of retirement for one final case, a much older and more contemplative figure.

Maybe Doyle had stopped fighting Holmes. Maybe he’d made peace with the character who made him immortal. The later stories feel different, less mechanical, more human. There’s a sense that Doyle finally accepted his role as Holmes’s chronicler rather than resenting it.

Doyle was knighted in 1902, officially for his work on a pamphlet justifying British action in the Boer War. But everyone knew the real reason. Sherlock Holmes had made him a national treasure. The detective created a vision of British rationality and justice that resonated far beyond the pages of The Strand Magazine.

The Legacy of a Reluctant Partnership

Doyle died in 1930, still known primarily as the creator of Sherlock Holmes. His historical novels are mostly out of print. His spiritualist writings are curiosities. But Holmes endures.

In a way, Doyle’s prediction came true. He’s remembered for Holmes. But he’s also immortal because of Holmes. How many historical novelists from the 1890s can you name? How many Victorian magazine writers are still read today?

The relationship between creator and creation is always complicated. Doyle gave the world Holmes, then tried to take him away, then reluctantly gave him back. And in that struggle, something interesting happened. Holmes became more than just a character. He became an idea, a template, a cultural touchstone.

A Fictional Ghost Who Refuses to Die

Today, Holmes is more alive than ever. He’s been played by everyone from Basil Rathbone to Benedict Cumberbatch. He’s been reimagined, modernized, parodied, adapted for radio, TV, film, and comics. There’s “House,” a medical show that’s basically Holmes as a doctor. There’s “Elementary,” which made Watson a woman. There’s the Robert Downey Jr. films, which turned Holmes into an action hero.

And still, somehow, he remains Holmes. The core survives every adaptation: the deductive reasoning, the social awkwardness, the loyalty between Holmes and Watson, the fog and mystery of Victorian London even when the setting moves to modern New York or BBC’s contemporary London.

The Baker Street Irregulars, founded in 1934, is still the premier Sherlock Holmes society. Scholars still publish academic papers analyzing the stories. Tourists still visit 221B Baker Street in London, where a museum occupies the address that didn’t technically exist when Doyle was writing.

Why Doyle Had to Bring Him Back

So why did Doyle have to bring him back? Because Sherlock Holmes wasn’t just Doyle’s creation anymore. He belonged to the readers. He lived in their minds, their imaginations, their idea of what a detective should be. And no author, not even the one who wrote the words, could kill him for good.

This was one of the first examples of fandom as we understand it today. Victorian readers didn’t just passively consume Holmes stories. They demanded more. They mourned his death. They rejected his creator’s authority to end the story. They forced a resurrection through sheer collective will and economic pressure.

Every time a beloved TV show gets canceled and fans campaign for its return, they’re channeling those Victorian readers who wore black armbands for a fictional detective. Every time a franchise gets revived because of fan demand, that’s the echo of what happened with Holmes.

Doyle learned what every creator eventually learns: once you send your work into the world, it’s not entirely yours anymore. It belongs to the people who love it, who see themselves in it, who need it to continue existing.

And maybe that’s not such a bad legacy. Arthur Conan Doyle wanted to be remembered as a serious novelist. Instead, he’s remembered as the man who created the world’s most famous detective, who tried to kill him, failed, and then spent the rest of his career reluctantly serving the character who refused to die.

In the end, Holmes won. And we’re all better for it.

Sources:

1. Arthur Conan Doyle, The Final Problem (1893)

2. Arthur Conan Doyle, The Adventure of the Empty House (1903)

3. Lycett, Andrew. The Man Who Created Sherlock Holmes: The Life and Times of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle