He was a soldier, a prisoner, a runaway, and eventually… a Cherokee. Not by blood, but by bond.

Ludovic Grant’s life sounds like something out of a historical novel, but almost no one remembers his name. That’s wild, considering he helped shape the relationship between Scotland, Britain, and the Cherokee in the 18th century, and left a legacy that rippled through generations, including one that would lead to a U.S. president. Well, a Cherokee president, at least.

From Highland Battles to Colonial Backwoods

Grant was born in Scotland, sometime around 1690, in the rugged Highlands where clan loyalty meant everything and the Stuart dynasty still had fierce supporters. He fought in the Jacobite uprising of 1715, supporting the Stuart cause against the Hanoverian succession. These weren’t just political disagreements. These were battles for the soul of Scotland, for whether the country would remain tied to its Catholic past or embrace the Protestant future that England demanded.

Spoiler: the Stuarts lost. Badly.

Grant was captured at the Battle of Preston in November 1715, one of thousands of Jacobite rebels who surrendered after a failed siege. He was marched south in chains, imprisoned in dank English jails where many of his fellow Scots died of disease and neglect. The lucky ones were executed quickly. The unlucky ones faced transportation.

Here’s where the story turns. Instead of rotting in jail or being hanged as a traitor, Grant was transported to the American colonies as punishment. Think of it as 18th-century exile with a labor contract attached. From rebel to indentured servant, he landed in Charles Town (now Charleston, South Carolina), probably bitter, definitely broke, and still nursing old loyalties to a cause that no longer existed.

Transportation wasn’t a kindness. It was a different kind of death sentence. You’d spend seven to fourteen years working off your passage, often in brutal conditions on plantations or in workshops. Many didn’t survive. Those who did emerged with nothing but scars and the knowledge that they could never go home.

But something changed in Ludovic Grant.

A Trader Among the Cherokee

By the 1720s, Ludovic Grant had re-emerged as a trader in Cherokee territory. That alone is a massive pivot. It meant leaving behind the coastal British world of plantations, propriety, and power, and entering the rugged, sovereign domain of the Cherokee Nation. Different highlands, different rules, different kind of survival.

And he wasn’t just trading beads and knives for pelts. Grant learned the language, a complex tongue with sounds that English-speakers struggled to pronounce. He married into the tribe, taking a Cherokee wife whose name history didn’t bother to preserve (typical). He raised a family. Built a home. Participated in councils.

The Cherokee didn’t just tolerate him. They accepted him. That’s not a small thing. This was a period when most Europeans saw Native peoples as obstacles to expansion or convenient allies in colonial wars. True cultural integration was rare. It required humility, patience, and a willingness to become someone new.

Grant became that someone. He wasn’t an observer or an exploiter. He became part of the story, woven into the fabric of Cherokee society in ways that would echo for generations.

The trader’s life wasn’t romantic. It was hard, dangerous work. You traveled through wilderness with packs of goods, negotiated with different Cherokee towns that sometimes had conflicting interests, and navigated the constant tension between British colonial authorities and Cherokee sovereignty. One wrong move, one broken promise, and you could end up dead or banished from both worlds.

Writing from the Edge

What we know about early 18th-century Cherokee life comes in part from Ludovic Grant’s own words. In 1730, he wrote a long, detailed letter to James Glen, the Royal Governor of South Carolina. It’s not a dry merchant’s report full of inventory lists and profit margins. It’s vivid, personal, and layered with warnings about how British meddling might backfire spectacularly.

He wasn’t romanticizing the Cherokee. He was just being honest, which was rare for the time.

His letter gives us an inside look at tribal politics, internal rivalries, diplomatic customs, and cultural practices at a time when outsiders rarely understood (or cared to understand) what they were seeing. Grant described everything from how Cherokee councils made decisions to how trade disputes were resolved to the delicate balance of power between different Cherokee settlements.

He wrote about the matrilineal clan system, where children belonged to their mother’s clan and inheritance passed through women, not men. He explained the role of Beloved Women in Cherokee governance, powerful female leaders who could overrule war councils. He detailed the Green Corn Ceremony and other rituals that structured Cherokee spiritual life.

This wasn’t anthropology, exactly. It was the observations of someone living inside the culture, someone whose children were Cherokee, someone who had a stake in both worlds understanding each other better.

It’s one of the earliest written European accounts that treated the Cherokee as complex people with sophisticated political systems and rich cultural traditions, not just obstacles to colonial expansion or convenient allies in wars against the French.

A Legacy Carved Into Cherokee History

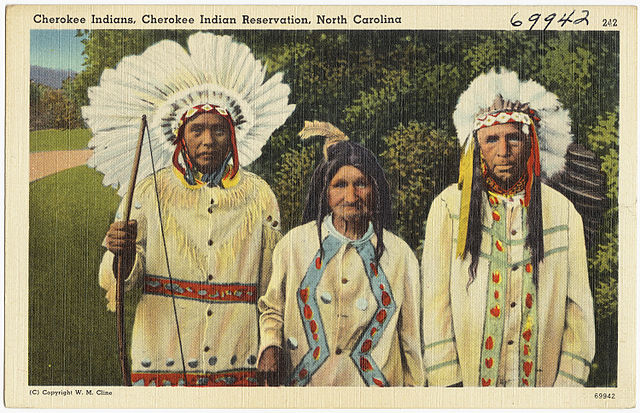

Today, the legacy of Ludovic Grant lives on not only through the stories of his descendants but also through the continued prominence of his bloodline within Cherokee leadership. Many Cherokee chiefs and leaders trace their ancestry back to Ludovic Grant, whose decision to marry into the Cherokee Nation centuries ago set in motion a lineage of leaders and advocates for the Cherokee people.

Grant’s children were raised Cherokee. They spoke Cherokee as their first language. They belonged to their mother’s clan. They participated in ceremonies and dances. They hunted and farmed and lived according to Cherokee customs. But they also carried Scottish blood, European features, and connections to the colonial world that would prove both advantageous and complicated in the decades to come.

The blend of Scottish and Cherokee heritage found in Grant’s descendants is a testament to the complexities of identity, survival, and resilience in a world that increasingly demanded people choose sides. Mixed-heritage Cherokee families often found themselves in impossible positions, trusted fully by neither the Cherokee councils nor the white settlers, yet essential to navigation between both worlds.

Caught Between Worlds

Grant walked a tightrope his entire adult life. He saw the creeping danger of colonial expansion, the way settlers pushed further into Cherokee territory every year, the way British promises meant less and less. But he also understood the fragile alliances that held peace together, the trade relationships that brought goods the Cherokee had come to depend on, the diplomatic channels that sometimes prevented all-out war.

He knew British ambitions wouldn’t stop at trade. He’d seen empire up close, fought against it, been crushed by it. He understood what was coming.

But he stayed.

Through the 1740s and beyond, Grant continued living among the Cherokee. His mixed-heritage children were raised in both cultures, speaking both languages, navigating both worlds. He built bridges, not perfectly, not without flaws or contradictions, but with sincerity and commitment that most traders never bothered with.

He witnessed the slow erosion of Cherokee autonomy. The increasing pressure from settlers. The cynical maneuvering of colonial governors who played Cherokee factions against each other. The whiskey trade that devastated communities. The diseases that killed thousands.

And through it all, he remained, raising his family, maintaining his trade networks, writing his letters, trying to explain each world to the other.

The Grandson Who Became a President (Kind Of)

John Ross, born in 1790, was Ludovic Grant’s grandson through Grant’s daughter. He would go on to become the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation during its most painful and defining era, the Trail of Tears.

Ross was only one-eighth Cherokee by blood. He had light skin, blue eyes, and could pass for white without question. But he was raised Cherokee, spoke the language fluently, and identified completely with his mother’s people. When the crisis came, when the U.S. government demanded Cherokee removal from their ancestral lands, Ross didn’t use his appearance to escape west while his people suffered.

He fought. Hard.

Ross fought the removal policies of the U.S. government with everything he had. He led his people in court, taking cases all the way to the Supreme Court and winning (the Court ruled in favor of Cherokee sovereignty, and President Andrew Jackson ignored the ruling). He lobbied Congress endlessly, giving speeches, writing petitions, meeting with anyone who might help. He hired lawyers, submitted documents, used every legal mechanism available.

And finally, when all political and legal options were exhausted, he led his people into exile. In 1838, over 16,000 Cherokee were forced to march west to Indian Territory (now Oklahoma). Thousands died along the way from cold, hunger, disease, and despair. Ross’s own wife, Quatie, died on the Trail after giving her blanket to a sick child.

And while John Ross looked more European than Indigenous, his heart, his language, his home, his loyalty, were Cherokee. He served as Principal Chief for nearly 40 years, guiding the Cherokee through their darkest period and helping them rebuild in the West.

Would John Ross have existed without Ludovic Grant? Probably not. It’s a strange twist of history. A Scottish rebel exiled to America becomes a Cherokee patriarch. His grandson becomes one of the most powerful and respected Native leaders of the 19th century, fighting against the same kind of empire his grandfather once rebelled against.

What Do We Do With Stories Like This?

It’s tempting to make Grant a hero. Or a symbol of cultural bridge-building. Or to romanticize his choice to “go native” as some kind of noble rejection of empire.

But he was just a man. Complicated, inconvenient, in-between. He lived in the margins and tried to make something good out of it. He was probably motivated by survival as much as principle. He benefited from trade relationships even as he witnessed their destructive effects. He straddled worlds without fully belonging to either.

That might be the most honest legacy of all.

History isn’t always about empires or battles or the grand sweep of nations. Sometimes, it’s about the quiet, stubborn lives of people who didn’t fit neatly into either side. People who crossed lines, married across cultures, and tried to listen more than they spoke.

Ludovic Grant didn’t conquer anything. He didn’t write laws or raise armies or sign treaties that changed borders. But he listened. He learned. And he stayed. He raised children who carried both worlds forward. He wrote down what he saw with honesty and clarity. He built relationships based on respect rather than exploitation.

And in doing that, he helped shape a story much bigger than himself. A story about what it means to belong, to adapt, to survive when the world keeps trying to force you into categories that don’t fit. A story that led to John Ross, to Cherokee resilience, to a lineage that refused to disappear even when empire demanded it.

Next time someone talks about the Trail of Tears or Cherokee history, remember that it starts with individual choices made centuries before. With a Scottish rebel who became a Cherokee trader. With marriages that crossed cultures. With children raised between worlds. With the complicated, messy, beautiful reality of people who refused to be just one thing.

Sources:

1. Grant, Ludovic. Letter to Governor James Glen (1730). South Carolina Archives.

2. Perdue, Theda, and Green, Michael D. The Cherokee Nation and the Trail of Tears. Penguin Books.

3. McLoughlin, William G. Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic. Princeton University Press.