On August 29, 1911, a starving man stepped out of the wilderness and walked into Oroville, California. His hair was singed short, a traditional sign of mourning among his people. He was wrapped in rags and looked like a ghost. People panicked. They thought they were seeing a phantom from the past. And in a way, they were.

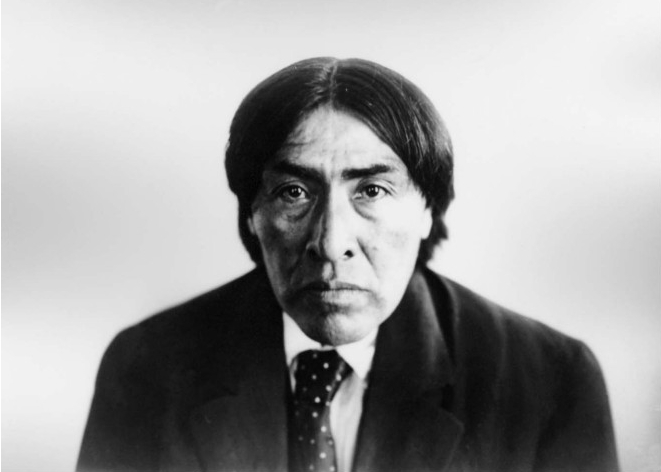

That man was Ishi. And he was the last known member of the Yahi people.

A Vanishing World

For years, the Yahi had been hiding in the rugged hills of Northern California, evading settler encroachment, the Gold Rush, and the genocidal violence that decimated so many indigenous groups in the West. Ishi was not the first to escape. In fact, his family had been killed by settlers years before, hunted down in what locals called “Indian hunting parties.” The survivors lived in isolation, hiding from the outside world, and largely from history itself.

Ishi’s appearance on the outskirts of the town of Oroville in 1911 was a moment of desperation for him, yet also an unimaginable act of courage. He had spent his entire life being taught that contact with white settlers meant death. And he wasn’t wrong. But starvation changes the calculus. When you’re dying anyway, maybe walking into the world that destroyed your people becomes the only option left.

The slaughterhouse workers who found him thought he was insane or dangerous. They called the sheriff. Ishi was too weak to run, too exhausted to resist. He just stood there, waiting to see what would happen next.

The Death of a Tribe

Imagine this: you’re the only person left who speaks your language. The only one who remembers the old songs, the names of rivers, how to hunt in silence, how to make fire with sticks and stone. Everyone you ever knew is gone. Killed. Starved. Scattered. You’re the last thread in a tapestry being pulled apart.

That was Ishi’s world.

The Yahi were part of the Yana people, a group of Indigenous Californians who lived in the foothills and canyons of the Sierra Nevada. Before the Gold Rush, there were thousands of them, maybe as many as 3,000, living in villages along Deer Creek and Mill Creek. They had their own distinct language, customs, and territory. They knew every edible plant, every animal migration pattern, every source of water in their homeland.

But then came 1849. And with it, came miners, settlers, disease, guns, and a government that paid money for Native scalps. Yes. Paid. Money. For scalps. California actually reimbursed citizens for “expenses” related to killing Native Americans. Militia groups organized weekend hunting parties. Men would ride into the hills specifically to kill indigenous people, then submit receipts to the state government.

By the late 1800s, the Yahi were presumed extinct. Newspapers ran stories celebrating the disappearance of the “wild Indians” from the region. But they weren’t extinct.

They were hiding.

The Hidden Years

For over 40 years, Ishi and a tiny group of surviving relatives lived in hiding. At most, there were about a dozen of them. His mother. His sister. A few others. They built shelter in remote canyons, camouflaged so well that hunters passed within feet without noticing. They only moved at night. They left no trace, no footprints, no broken branches, nothing that would reveal their presence. They watched the world from the shadows, knowing it would destroy them if it saw them.

They survived on salmon from the creeks, acorns they processed into meal, deer they hunted with bows made in absolute silence. Every fire had to be small enough that the smoke wouldn’t be visible. Every sound had to be controlled. Children, if there had been any, would have been taught from birth never to cry, never to laugh too loud, never to forget that discovery meant death.

The group grew smaller. Disease took some. Starvation took others. In 1908, a surveying party stumbled upon their camp while the group was away. The surveyors ransacked everything, taking tools, baskets, food stores. Ishi’s mother was too sick to flee and had to hide under blankets. When Ishi returned and found the camp destroyed and his mother traumatized, something broke in the group.

Then one day, Ishi was alone. The others had died. Illness, starvation, grief. His mother went last, too weak to continue. He burned their bodies in the old way, cutting his hair short in mourning. Then, desperate and with no reason left to hide, he walked into town.

The Man Who Shouldn’t Have Existed

The people of Oroville didn’t know what to do with him. He didn’t speak English. He didn’t even speak Spanish. He had no money, no papers, no past the white world could understand. Authorities put him in jail for his own protection, more confused than hostile. Local newspapers ran sensational headlines about the “wild man” discovered in the foothills.

But news traveled fast. Anthropologists from the University of California heard about the discovery and came immediately to meet him. One of them, Alfred Kroeber, realized the enormity of what had just happened: this man was a living link to a world thought lost. He could speak a language no linguist had ever recorded. He knew technologies and survival techniques that existed nowhere else.

Kroeber and his colleague Thomas Waterman worked to communicate with Ishi, eventually finding enough common ground through other Native languages to establish basic dialogue. They called him “Ishi,” which just means “man” in Yana. It wasn’t his real name. Ishi never revealed his real name, as speaking your own name aloud was taboo in Yahi culture. To speak it would be to diminish its power, to make yourself vulnerable. So “Ishi” he became, the generic name, the placeholder for an identity that died with his people.

A Living Museum Exhibit

Kroeber brought Ishi to San Francisco. He lived at the university’s museum of anthropology, where he worked as a janitor and, heartbreakingly, as a living exhibit. The museum set up a special area where Ishi would demonstrate traditional Yahi skills on Sunday afternoons. Crowds came to watch him make arrowheads, how to start a fire with a bow drill, how to shape obsidian tools with precision that amazed modern craftsmen.

He wasn’t bitter. At least, not outwardly. He was patient. Quiet. Kind. He adapted to city life with remarkable grace. He liked smoking cigarettes and eating roast beef. He was fascinated by matches and light switches. He took the streetcar and seemed to enjoy watching the city bustle around him. He made friends among the museum staff and researchers. He loved children and would patiently show them how to craft tiny bows and arrows.

And yet, he was always alone. Truly alone in a way that’s hard to comprehend. There was no one on Earth who shared his childhood memories. No one who knew the same songs his mother sang. No one who could speak his language as a peer, only as clumsy students trying to preserve fragments of something living.

Imagine being admired for your skill in making tools your people once needed to survive, while knowing your people are gone. Imagine demonstrating how to flake obsidian while inside your head you’re remembering your sister doing the same thing, your mother teaching you the technique, all of them dead now, and you’re performing their memory for strangers who will never truly understand what was lost.

The anthropologists, particularly Kroeber and Dr. Saxton Pope (a physician who became close to Ishi), tried to treat him with dignity. They took him on camping trips back to his homeland. They recorded hours of his language, his stories, his knowledge. Pope learned archery from him and later wrote a book about traditional Native American bow hunting, crediting Ishi as his teacher.

But there’s no escaping the exploitation embedded in the arrangement. Ishi lived in a museum. He was studied. Measured. Recorded. However kind his caretakers were, he was still fundamentally a specimen, the last of his kind, valued for what he represented rather than who he was.

Ishi’s Final Days

In 1916, just five years after he emerged from the wilderness, Ishi died of tuberculosis. The disease had ravaged Native communities for decades, spread by the same settlers who took their land. His immune system, isolated from common diseases for a lifetime, didn’t stand a chance.

Kroeber was traveling in the East Coast when Ishi fell ill. He sent urgent telegrams demanding that if Ishi died, there should be no autopsy, no desecration of his body. Indigenous remains had been treated as scientific property for too long. Ishi deserved better.

Despite Kroeber’s wishes, doctors at the hospital performed an autopsy anyway. They removed Ishi’s brain and sent it to the Smithsonian Institution, where it sat in storage for decades. This, after a life defined by dignity, silence, survival. Even in death, the institutions that claimed to honor him treated him as a specimen first and a person second.

It wasn’t until 2000, after years of advocacy from Native American groups and descendants of the Yana people, that Ishi’s remains were finally returned and laid to rest in a secret location, protected from further disturbance.

The Last Voice

Ishi’s life was a tragedy. But it was also a testimony.

Through him, we caught a fleeting glimpse of a world wiped out in silence. He showed us what was lost. And what could still be remembered. He spoke Yahi for the last time, and researchers recorded hours of it on wax cylinders. Those recordings still exist, scratchy and faint, the last echoes of a language that will never be spoken again as a living tongue.

He taught the old ways to anyone willing to listen. How to track deer by reading disturbances in grass and soil. How to make fish hooks from bone. How to predict weather from the behavior of birds. How to live with almost nothing and still maintain beauty, craft, and dignity.

He didn’t want to be famous. He just wanted to live, and he did so with grace under circumstances that would have broken most people. Saxton Pope wrote about Ishi’s perpetual gentleness, his humor, his curiosity about the modern world mixed with quiet sorrow for what was gone.

What Ishi Left Behind

His story isn’t about the past. Not really. It’s about how the past haunts the present. It’s about how survival can look quiet, even invisible. It’s about how being the last doesn’t mean being forgotten.

The genocide of California’s Native peoples is one of the least discussed chapters of American history. Between 1846 and 1873, California’s Native population dropped from around 150,000 to less than 30,000. That’s not war. That’s systematic extermination. Ishi’s story puts a face on those statistics, makes them real in a way numbers never can.

Today, the recordings of Ishi’s voice, his demonstrations of traditional skills, and the artifacts he created are housed in museums and universities. They’re valuable, yes. But they’re also heartbreaking. They represent a man who became a bridge between worlds, not by choice but by circumstance, the sole survivor of a genocide explaining to his people’s destroyers what was destroyed.

Next time you hear about “the last speaker of a language” or “the end of a culture,” remember Ishi. Remember what it actually means to be the last. The loneliness. The weight. The impossible task of preserving an entire world inside one human memory.

And remember that Ishi walked into Oroville not because he wanted to join the modern world, but because he had nowhere else to go. His courage wasn’t in embracing a new life. It was in choosing to keep living at all.

Sources:

1. Heizer, Robert F., and Theodora Kroeber. Ishi in Two Worlds. University of California Press.

2. Smithsonian Institution Archives

3. Native American History of Northern California