Imagine walking into a hospital in the 1800s. Not a sleek, sanitized, beep-filled building with hand sanitizer dispensers every ten feet. Think bloodstained aprons worn with pride, surgeons reusing scalpels without even wiping them down, and a faint smell of decay that just kind of hangs in the air like an unwelcome guest.

That was normal. Surgery was basically a game of survival, and the house usually won.

Then came Joseph Lister. And everything changed.

The Bloody Truth About Surgery Back Then

Before Lister, surgery was fast, brutal, and horrifyingly filthy. Surgeons prided themselves on speed, not cleanliness. The faster you could amputate a leg, the better surgeon you were. Some could do it in under a minute. They timed themselves.

They wore the same unwashed coat for every operation, stiff with dried blood and pus from previous patients, like a badge of honor. The more crusted and stained your surgical coat, the more experienced you were considered. New doctors with clean coats were rookies. Veterans looked like they’d been through a war.

People believed infections were caused by “bad air” or miasma, invisible poisonous vapors that rose from rotting matter. Or they just chalked it up to bad luck, divine punishment, or the patient’s weak constitution. Not by, say, the literal bacteria crawling on their tools, their hands, and embedded in the fibers of those disgusting coats.

One in every two surgical patients died from infections like sepsis or gangrene. That’s a 50% mortality rate. Flip a coin. Heads you live, tails you die from an infection days after a successful procedure. Hospitals were nicknamed “death houses” and “gateways to the grave.” Soldiers in wartime often had better survival rates on the battlefield than in the military hospitals.

Doctors were basically winging it. They had skill, sure. They understood anatomy. But they had no concept of germs or sterilization. And patients paid the price in agony and death.

Enter the Clean Freak Nobody Asked For

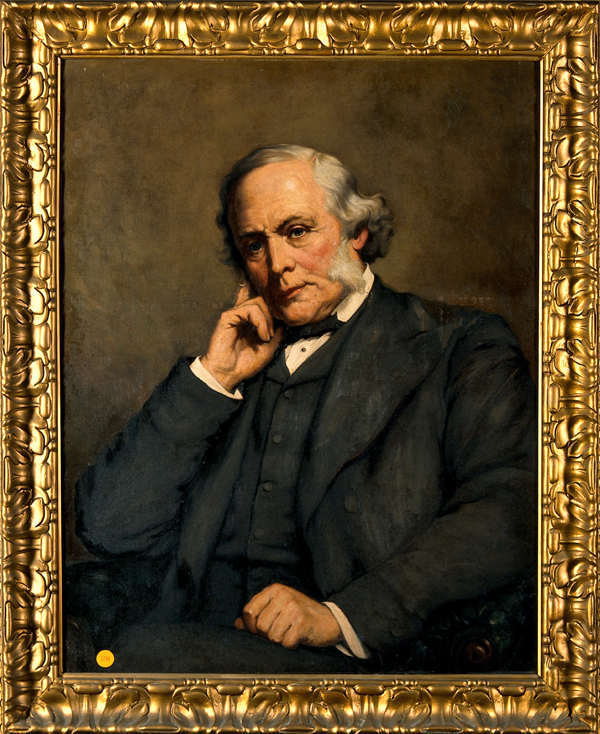

Joseph Lister was a British surgeon working in Glasgow in the 1860s, and unlike most of his colleagues, he actually believed that invisible stuff might be killing people. This wasn’t just a hunch. He’d been reading.

Inspired by Louis Pasteur’s work on germs, Lister had this crazy idea: What if microscopic organisms were responsible for infection? What if those tiny living things Pasteur found in spoiled milk and wine were also getting into wounds and causing them to fester and rot?

And what if, hear me out here, we cleaned our instruments and wounds to kill these organisms?

People thought he was nuts. Germs were a fringe theory. Most doctors didn’t even own microscopes. The idea that you couldn’t see the thing killing your patients seemed absurd to the medical establishment.

But Lister was stubborn. He started experimenting with carbolic acid (phenol), a chemical used to clean sewage and reduce the stench in cesspools. If it worked on waste and killed whatever was causing the smell, maybe it could work on wounds and kill whatever was causing infections.

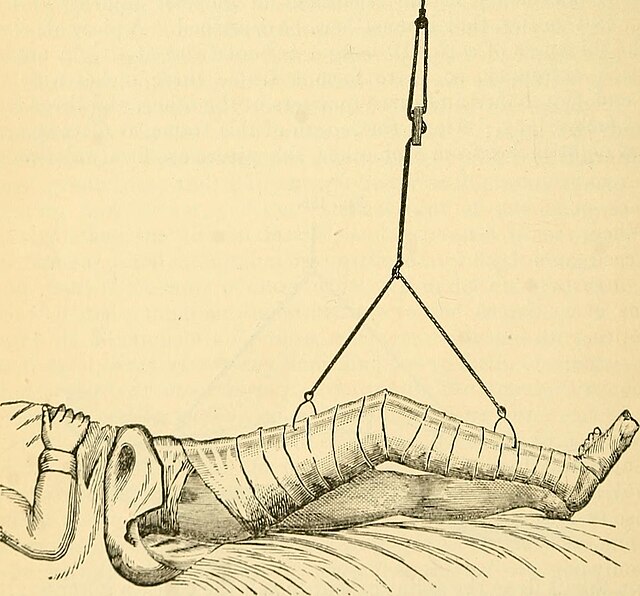

So he soaked dressings in carbolic acid. He cleaned surgical tools with it. He washed his hands in diluted solutions. He even built a machine to spray a fine mist of carbolic acid in the air during surgery, creating a cloud of disinfectant around the operating table.

It stank like industrial cleaner. It burned the skin if you weren’t careful. Nurses complained. Patients wrinkled their noses. It was, in his words, “an antiseptic method.”

And it worked. Like, dramatically worked.

His first major success came in 1865 when he treated an 11-year-old boy with a compound fracture, where the broken bone had pierced the skin. These injuries almost always led to amputation or death from infection. Lister dressed the wound with carbolic acid-soaked bandages. The boy healed completely. No infection. No amputation. The leg was saved.

Mortality rates in Lister’s ward plummeted from nearly 50% to around 15%. Patients stopped dying from infections. Wounds healed cleanly. Amputations became less necessary. It was like magic, except it wasn’t magic. It was science. And soap. And some good old Victorian stubbornness.

The Medical World Was… Not Impressed

You’d think everyone would jump on board immediately, right? They didn’t. In fact, Lister’s colleagues mocked him openly. Some refused to believe tiny organisms they couldn’t even see could do anything, let alone kill people. Others just didn’t want to change their habits or admit they’d been doing it wrong for their entire careers.

Old-school doctors scoffed at the whole concept. They were like, “We’ve been cutting people open for centuries. Why start washing now?” The medical establishment was deeply conservative. These were men who’d trained under surgeons who’d trained under other surgeons going back generations. Tradition mattered more than evidence.

Some doctors tried Lister’s methods once, didn’t follow the protocol correctly, got poor results, and declared the whole thing nonsense. Others resented the implication that they’d been killing their patients through negligence. The ego couldn’t handle it.

There was also the practical problem: carbolic acid was unpleasant to work with. It irritated skin. The spray machine was cumbersome. The whole process took more time. Surgery was slower, more methodical. For doctors who prided themselves on speed, this felt like a step backward.

But Lister didn’t stop. He kept publishing papers, giving lectures, showing his results to anyone who would listen. He refined his techniques, finding better ways to apply antiseptics that were less harsh. He documented everything meticulously, building an undeniable body of evidence.

Slowly, painstakingly, his methods spread. Hospitals in Germany started using antiseptics. American surgeons began experimenting with his techniques. Young doctors, less set in their ways, embraced the new approach.

The Tide Finally Turns

By the late 1800s, surgery had transformed completely. The idea of sterile environments became standard practice. Gloves became mandatory. Clean tools went from optional to required. Disinfected rooms, surgical masks, hand washing, all the things we take for granted today, emerged from Lister’s work.

Interestingly, Lister’s methods eventually evolved into something even better: aseptic surgery. Instead of just killing germs with chemicals (antiseptic), surgeons started preventing germs from getting there in the first place (aseptic). Steam sterilization of instruments, autoclaves, sterile gowns, surgical caps, the whole modern operating room setup emerged from this shift.

And Lister? He got recognition, eventually. He was appointed Surgeon to Queen Victoria. He got a title, Lord Lister, becoming Baron Lister of Lyme Regis. The Queen gave him a baronetcy in 1883. Not bad for a guy who just wanted doctors to wash their hands.

He became president of the Royal Society, one of the most prestigious scientific positions in Britain. Medical schools taught his methods. Hospitals around the world adopted antiseptic protocols. By the time he died in 1912, his ideas had become so standard that young doctors couldn’t imagine medicine without them.

Why It Still Matters

Today, it seems obvious. Of course we sterilize instruments. Of course we scrub in before surgery. Of course we wear gloves and masks. But it wasn’t always obvious. Someone had to fight for it against massive institutional resistance and professional mockery.

Lister’s story is a reminder that progress often starts with one person asking, “Wait, what if we’re doing this wrong?” One person willing to look at standard practice and say, “This is killing people, and I don’t care if everyone thinks I’m crazy.”

He didn’t invent germs. Pasteur and others discovered microorganisms. But Lister gave medicine a mirror, forced it to look at its own practices, and what it saw wasn’t pretty. Blood-soaked coats. Filthy instruments. Preventable deaths by the thousands.

And that spray machine? Basically a 19th-century disinfectant cannon. Weirdly impressive for its time, even if it looked ridiculous and made everything smell like a chemical plant.

The Quiet Revolution

What’s fascinating about Lister’s revolution is how quiet it was compared to other medical breakthroughs. There was no dramatic moment, no single surgery that changed everything overnight. Just steady, persistent application of a better method until the evidence became undeniable.

The modern operating room exists because of him. Every time a surgeon scrubs in, every time a nurse opens a sterile instrument pack, every time someone survives an operation without infection, that’s Lister’s legacy.

It’s estimated that antiseptic and aseptic techniques have saved hundreds of millions of lives since their adoption. Maybe billions, when you count all the surgeries, all the wars, all the medical procedures that would have been death sentences in the pre-Lister era.

So the next time you’re in a hospital and everything smells like cleaning solution and latex gloves, thank Joseph Lister. He turned the tide in one of humanity’s bloodiest battles: the war against infection. He proved that sometimes the answer isn’t more dramatic surgery or faster techniques. Sometimes it’s just washing your damn hands.

And he did it while everyone told him he was wrong. That takes a special kind of stubborn. The good kind. The kind that saves lives.

Sources:

1. “Joseph Lister: The Man Who Made Surgery Safe”

2. Porter, Roy. The Greatest Benefit to Mankind: A Medical History of Humanity (1997)

3. Fitzharris, Lindsey. The Butchering Art: Joseph Lister’s Quest to Transform the Grisly World of Victorian Medicine (2017)

4. Science Museum UK

5. Britannica: Joseph Lister