Mongol tents pitched beneath the vast Central Asian sky. Inside, a Buddhist monk, a Christian priest, and a Muslim scholar sit across from each other, arguing theology before one of history’s most powerful empires.

It sounds like the setup to a bad bar joke, but this really happened. And not just once. In the 13th century, the Mongols, yes, the horse-riding, empire-conquering Mongols, held public religious debates between faith leaders. With translators. With crowds. With judges. With actual rules about being respectful.

This wasn’t a footnote in history. This was the world’s first known interfaith forum backed by the might of a superpower. And it’s one of the weirdest, wildest, most unexpectedly progressive stories from an empire better known for blood than dialogue.

Wait, the Mongols Did What Now?

After Genghis Khan’s death in 1227, his successors ruled over the largest contiguous empire the world had ever seen. From the Pacific Ocean to the edges of Europe, the Mongols controlled lands filled with Buddhists, Muslims, Nestorian Christians, Catholics, Daoists, Jews, and shamanists.

Rather than force everyone into one faith, which is what most empires before and after them did, the Mongols tried something different. They invited leaders of different religions to the capital, especially under the rule of Mongke Khan in the 1250s, and told them to make their case.

The goal? Truth. Or at least, some kind of usable wisdom. The Mongols loved competitions of all sorts, and they organized debates among rival religions the same way they organized wrestling matches. They were deeply pragmatic. They believed that if a religion had real power, it should be able to prove itself. Not with swords, but with reason.

The Religious Tolerance Nobody Expected

The Mongol approach to religion was unusual for its time. They believed in Tengri, a sky god, but weren’t dogmatic about it. Mongol shamanism was flexible enough to accommodate other spiritual practices. More importantly, the Mongols saw religion as potentially useful, something that could bring knowledge, healing, or favor from the divine.

Mongke Khan’s mother was a Nestorian Christian. His court included Muslim advisors, Buddhist monks, Daoist priests, and Christian clergy from multiple denominations. Rather than seeing this diversity as a threat, Mongke saw it as an opportunity. If these religions all claimed to have truth, why not have them compete to demonstrate it?

The Great Debate of 1254

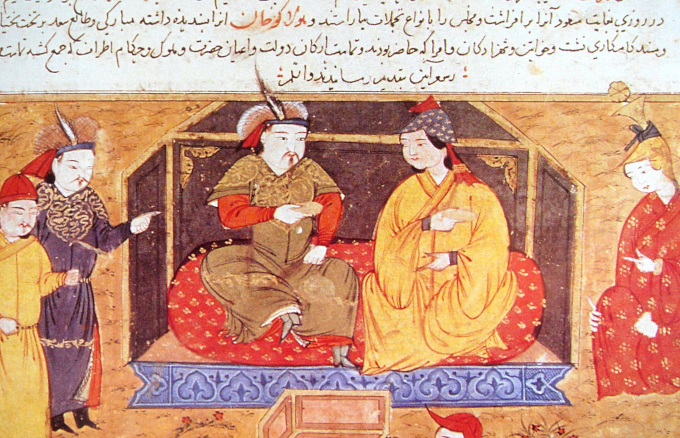

The most famous of these debates happened in May 1254 in Karakorum, the Mongol capital in what is now central Mongolia.

Mongke Khan summoned a Franciscan friar named William of Rubruck, who had been sent on a diplomatic mission by King Louis IX of France, along with Muslim scholars, Buddhist monks, and Nestorian Christian representatives, for what was essentially a no-holds-barred spiritual showdown.

Each side had translators. Each had a chance to argue their truth. Mongke Khan ordered them to debate before three judges: a Christian, a Muslim, and a Buddhist. A large audience assembled to watch the affair, which began with great seriousness and formality.

The Rules of Engagement

But here’s the twist: Mongke Khan imposed strict rules, announcing on pain of death that no one shall be so bold as to make provocative or insulting remarks to his opponent, and that no one is to cause any commotion that might obstruct these proceedings.

No cheap shots. No holy slander. No violence. Just arguments, logic, and a test of ideas. For the 13th century, when religious disagreements typically ended in bloodshed, this was revolutionary.

Rubruck, in his detailed letters back to King Louis IX, described the event in vivid detail. The debate ranged back and forth over topics of evil versus good, God’s nature, what happens to the souls of animals, the existence of reincarnation, and whether God had created evil.

How the Debate Actually Went Down

The debate started with the Buddhist monk asking fundamental questions about cosmology: how was the world made and what happens to souls after death? Rubruck countered that these were the wrong starting questions. He insisted they should begin by discussing God, from whom all things flow. The judges awarded the first round to Rubruck.

What’s fascinating is how the participants formed shifting coalitions. Rubruck and the other Christians joined together in one team with the Muslims in an effort to refute the Buddhist doctrines. On some topics, Christians and Muslims found common ground against the Buddhists. On others, the alliances shifted.

And here’s a detail that shows just how seriously the Mongols took their wrestling metaphor: Between each round of wrestling, Mongol athletes would drink fermented mare’s milk; in keeping with that tradition, after each round of the debate, the learned men paused to drink deeply in preparation for the next match. They were literally treating theology like a sport.

Why Did the Mongols Care?

Part of it was political. When you rule dozens of cultures, you can’t pick favorites too openly without risking rebellion or alienating important subject populations. Religious tolerance was pragmatic governance.

But part of it was sincere curiosity. The Mongols genuinely wondered which faith had the answers to life’s big questions. To them, it was almost scientific. Let the faiths compete, see which arguments hold up, and maybe learn something useful.

Also, they kind of loved chaos. And what’s more chaotic than pitting a priest against a monk against an imam and telling them to go at it, respectfully?

What Mongke Really Wanted

The day after the debate, Mongke Khan had a private audience with Rubruck. Mongke expressed what he hoped to achieve, telling Rubruck that God has given ways and religions to man as there are different fingers on one hand.

That statement is crucial. Mongke wasn’t looking for one faith to triumph and the others to be proven false. He was looking for coexistence, for a way to understand how different paths could all lead somewhere meaningful. No one “won” the debate in the traditional sense. That wasn’t the point.

Rubruck left thinking he’d defeated the Buddhists and Muslims with superior Christian logic. But the reality was more subtle. The other participants likely understood Mongol culture better than Rubruck did. They knew Mongke valued harmony and open-mindedness. So they debated respectfully, listened to each other, and avoided the kind of aggressive confrontation that might displease the Khan.

Faith Under the Tent: The Scene

Imagine it. Animal-hide tents flapping in the steppe wind. Tables covered with sacred scrolls and books in multiple languages. The smell of incense mixing with yak butter and fermented mare’s milk. A Franciscan friar in his simple brown robe, sitting across from Buddhist monks in saffron, Muslim scholars in fine robes, and Nestorian priests with their own distinctive garb.

Translators working frantically to convey complex theological concepts across Mongolian, Chinese, Arabic, Persian, and Latin. Mongol officials taking notes, trying to understand arguments about the nature of the soul, the problem of evil, and whether there’s one God or many.

It was surreal. But it happened. Multiple times, in fact. The 1254 debate wasn’t an isolated event.

The Other Debates

In 1255, Mongke Khan organized a debate between a Daoist leader named Li Zhichang and Buddhist master Fuyu, resulting in the decisive defeat of the Daoists. Mongke decreed that a Daoist text called the Huahu Jing, which disparaged Buddhism, should be banned and burned.

This shows another side of Mongol religious policy. They valued dialogue and tolerance, but they had limits. When one faith actively attacked another through propaganda, Mongke intervened. His principle was clear: religions should coexist peacefully, not undermine each other.

Later Mongol khans held similar debates in Persia and China, though none quite matched the scale or ambition of Mongke’s 1254 gathering. The practice of interfaith dialogue became part of Mongol court culture, a way of demonstrating the khan’s wisdom and cosmopolitan authority.

The Legacy We Forgot

We remember the Mongols for the cities they burned, the empires they destroyed, the millions who died during their conquests. The historical record emphasizes violence because violence makes for dramatic history.

But not for the conversations they started. Not for the unprecedented religious tolerance they practiced. Not for the fact that in 1254, while European Crusaders were still massacring Muslims and heretics, the Mongol Khan was hosting civilized theological debates with strict rules against insults.

These debates didn’t end war. They didn’t end persecution. Even under the Mongols, religious tensions existed. But they did something radical: they modeled respectful disagreement at the highest level of power. And they left behind a record of one of the first state-sponsored efforts to understand, not suppress, religious diversity.

What This Means for Us

In an era where people are still fighting over faith, where religious intolerance fuels conflicts across the globe, maybe we should all take a weird little note from the Mongols.

Sit down. Listen to each other. Argue with logic, not insults. Treat theological debate like a competition where the goal isn’t to destroy your opponent but to learn something. Drink some fermented mare’s milk between rounds if that helps.

The Mongols, of all people, figured this out in the 13th century. They weren’t saints. They conquered brutally and ruled pragmatically. But in this one strange practice, they got something right that we’re still struggling with today.

They proved that you can be the world’s most powerful empire and still make room for dialogue. That strength and curiosity aren’t opposites. That maybe, just maybe, the best way to understand the divine is to let everyone make their case and see what truth emerges from honest conversation.

Eight hundred years later, we could use a little more of that Mongol spirit. Not the conquering part. The listening part.

Sources:

1. William of Rubruck’s Journey to the East (Medieval Sourcebook)

2. “The Mongols and Religious Freedom” University of Pennsylvania

3. National Geographic: Genghis Khan and the Mongol Empire