Nostradamus: Prophet or Lucky Poet?

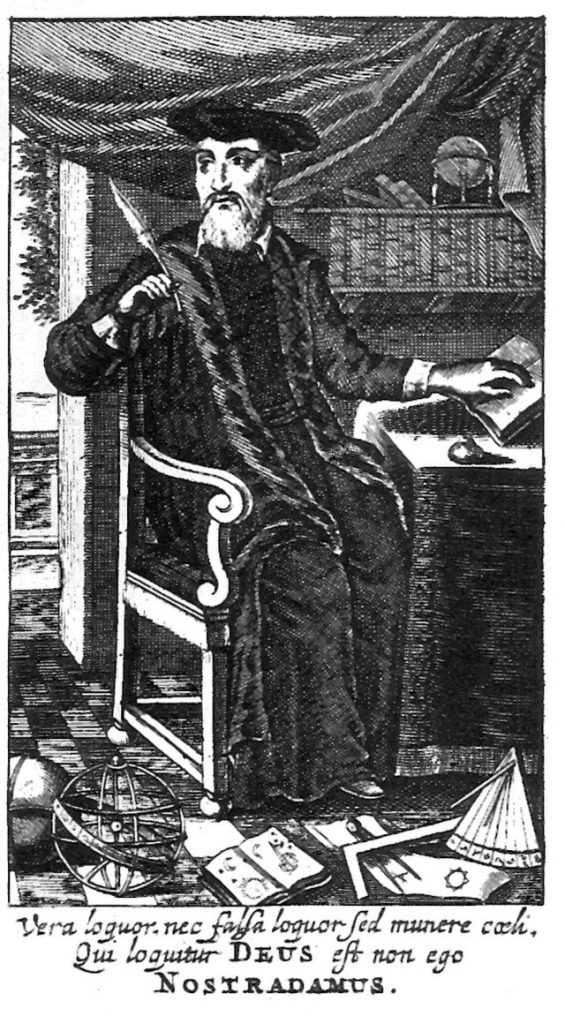

Picture this: a man in a candle-lit study, quill in hand, scribbling cryptic verses that would later have millions convinced he predicted the rise of Hitler, the 9/11 attacks, and maybe even the end of the world. Sounds like the plot of a Dan Brown novel, right? But nope. That was Michel de Nostredame, better known as Nostradamus.

The Man Behind the Mystery

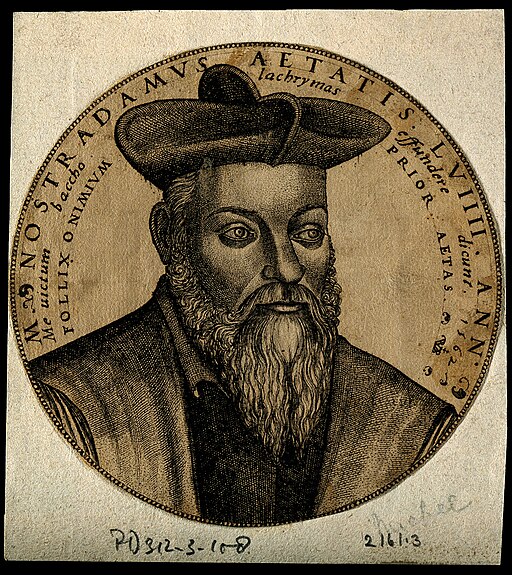

Born in 1503 in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, France, Nostradamus was a physician by trade and an astrologer by hobby (or maybe obsession). His early life was relatively normal for a Renaissance intellectual. He studied at the University of Avignon, then moved on to medical school at the University of Montpellier, where he earned his license to practice medicine.

Then the plague hit. Multiple times. And Nostradamus became something of a celebrity plague doctor, traveling from town to town treating victims with methods that were surprisingly progressive for the time. He advocated for fresh air, clean water, and removing corpses quickly rather than the bloodletting and prayers most doctors relied on. His remedies actually helped people survive, which was rare enough to build a reputation.

But the plague took its toll personally. His first wife and two children died during an outbreak, probably in the late 1530s. The tragedy shattered him. Worse, his in-laws sued him for the return of his wife’s dowry, and the Catholic Church started questioning his religious orthodoxy after he made some ill-advised comment about a religious statue.

After surviving the plague and losing much of his family to it, he took a turn toward the mysterious. He wandered Europe for years, possibly studying occult practices, definitely reading everything he could about astrology, alchemy, and ancient prophecies. When he finally settled down again in Salon-de-Provence and remarried, he started publishing almanacs filled with predictions, weather forecasts, and agricultural advice.

These were popular. Really popular. And that success gave him the confidence to go bigger. In 1555, he published Les Prophéties, a collection of 942 quatrains (four-line poems), written in a strange cocktail of French, Latin, Greek, Italian, and deliberately obscure language. That was his big claim to fame.

But here’s the thing: the verses are vague. Like, really, really vague. He didn’t say, “On September 11, 2001, terrorists will crash planes into towers in New York City.” Instead, he wrote things like, “Earth-shaking fire from the center of the Earth will cause tremors around the New City. Two great rocks will war for a long time.”

Hmm. Is that New York? Or maybe Naples (which means “new city” in Greek)? Or just an actual earthquake somewhere? The “two great rocks” could be anything. Buildings? Nations? Literal rocks? Your guess is as good as anyone’s.

Rorschach Test in Rhyme

Nostradamus’s quatrains are kind of like horoscopes: you see what you want to see. If something big happens, people dig into his verses to find something that kind of, sort of, if you squint and ignore half the words, fits. And surprise! They usually do. Because the language is metaphorical, non-sequential, and open-ended. It’s not prophecy. It’s poetry wearing a fortune-teller’s hat.

For example, many say he predicted Hitler by referring to “Hister” in one of his verses. Sounds close, right? The verse mentions a cruel leader from near the “Hister” who would bring war. Spooky! But here’s the problem: “Hister” was actually the Latin name for the Danube River, a major geographical feature Nostradamus would have learned about in school. Context matters. A lot.

People also claim he predicted the Great Fire of London in 1666 with a verse about “the blood of the just” being demanded in London and fire consuming the city. But fires were common in medieval cities built largely of wood. London had experienced major fires before 1666. Writing “a city will burn” in a world lit by open flames was less prophecy and more statistical probability.

The 9/11 prediction is even more convoluted. Believers cobble together fragments from multiple quatrains, add words that aren’t there, and ignore lines that don’t fit. One widely circulated “prediction” after 9/11 was completely fake, written by a college student in 1997 as an example of how easy it is to create vague Nostradamus-style prophecies.

Here’s how the game works: something dramatic happens, then prophecy hunters search through 942 quatrains looking for words like “fire,” “king,” “war,” “city,” “blood,” or “terror.” These words appear constantly because Nostradamus was writing during a period of religious wars, plague, and political instability. Of course his work is full of violence and disaster. That was just Tuesday in the 16th century.

So Why Do We Want to Believe Him?

Short answer? Humans hate uncertainty. Our brains are pattern-seeking machines, evolved to find connections even when they don’t exist. We want to believe someone saw it coming. It gives chaos a pattern, and that comforts us in a weird way. If disasters were predicted centuries ago, then maybe they were inevitable. Maybe they have meaning. Maybe the universe isn’t just random and terrifying.

Nostradamus offers just enough intrigue to make it feel like destiny was always written, hiding in plain sight. The vagueness is a feature, not a bug. Specific predictions can be proven wrong. Vague ones can never be definitively disproven.

Psychologists call this “confirmation bias” and “hindsight bias” working together. We remember the hits and forget the misses. We reinterpret his words after events to make them fit, then marvel at how accurate he was. But if we’d read those same verses before the events, we wouldn’t have known what they meant because they don’t actually mean anything specific.

Plus, let’s be honest, his stuff is fun to read when the world feels like it’s falling apart. During pandemics, wars, economic crashes, contentious elections, you name it, Nostradamus trends on social media. Like clockwork. Someone always finds a quatrain that seems relevant, shares it, and suddenly everyone’s convinced he predicted COVID-19 or World War III or whatever crisis is currently dominating the news cycle.

There’s also something democratizing about prophecy interpretation. You don’t need credentials or expertise. Anyone can read a quatrain and decide what it means. In an age where experts tell us complicated things we don’t understand, Nostradamus lets everyone be a prophet-interpreter.

His Actual Historical Influence

What’s fascinating is that Nostradamus was taken seriously by powerful people during his lifetime. Catherine de Medici, queen of France, became his patron after he supposedly predicted the death of her husband, King Henry II.

The story goes that Nostradamus wrote about “the young lion” defeating “the old” in combat, with a wound through the golden cage (helmet) causing death. In 1559, Henry II died after a jousting accident when a lance splintered through his helmet’s visor and pierced his eye. Close enough to be eerie, though jousting accidents were fairly common and describing one isn’t exactly supernatural foresight.

Sources:

1. Britannica – Nostradamus

2. History.com – Nostradamus