You’re in a toga, swatting flies with a palm fan, and someone named Marcus Terentius Varro leans over his scroll and casually suggests that disease might be caused by invisible creatures floating in the air.

Wait. What?

Before microscopes. Before Louis Pasteur. Before soap was even widely trusted. This Roman scholar predicted the existence of microorganisms. Actual microscopic agents of disease. And then the world kind of… ignored him for the next 1,900 years.

This is the wild, slightly dusty story of how a man born in the age of gladiators basically whispered germ theory into the void and why we’re only just now appreciating how weirdly ahead of his time he was.

Marcus Varro wasn’t wrong. He was ahead of his time by centuries.

Meet Marcus: Rome’s Most Underrated Genius

Marcus Terentius Varro wasn’t a doctor. He was a polymath. That’s Latin for “I know a little bit about everything and probably a lot more than you.” Born in 116 BCE, Varro wrote over 600 books (only a few survive), covering everything from language to farming to military tactics.

Think of him as a one-man Wikipedia. If Wikipedia also ran farms and fought in wars.

The man was relentlessly productive. He authored works on grammar that influenced Latin language studies for centuries. He wrote about Roman history, philosophy, architecture, music theory, and even created the first systematic encyclopedia known to Western civilization. His contemporaries included Cicero, who called him “the most learned of the Romans,” which is saying something when you’re living in the same era as Julius Caesar.

Varro served in the military under Pompey the Great, fighting pirates in the Mediterranean and later getting caught up in the Roman Civil War. When Caesar won, Varro wisely switched to focusing on his writing full-time. Smart move when your side loses and the victor is known for being, shall we say, unforgiving.

But his real “wait, what?” moment comes in a farming manual, the De Re Rustica, written around 36 BCE. It’s not even a medical text. It’s a guide for landowners on how to run a proper Roman estate.

And in the middle of this very sensible, soil-focused text, Varro drops a sentence that should’ve caused the world to double-take for centuries.

The Sentence That Should’ve Changed Everything

Here’s what Varro wrote, more or less:

“There are bred certain minute creatures which cannot be seen by the eyes, which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose, and there cause serious diseases.”

That’s it. That’s germ theory in a toga.

Tiny, invisible creatures. Floating in the air. Entering your body. Making you sick.

He wasn’t guessing about “bad air” or curses or miasmas. He literally describes microscopic organisms before the microscope even existed.

It’s like predicting TikTok during the invention of the printing press.

The context makes it even more remarkable. Varro was specifically writing about choosing healthy locations for farms and villas. He warned against building near swamps, not because of superstition or vague notions of bad air, but because he believed actual living creatures, too small to see, were breeding in these wet areas and causing illness.

This wasn’t mysticism. It was proto-scientific reasoning wrapped in practical advice. He even specified that these creatures entered through the mouth and nose, showing he understood transmission routes. That level of specificity suggests he’d thought deeply about how disease actually spread, not just that it happened mysteriously.

So… How Did He Know?

Here’s where things get interesting.

Varro didn’t know, obviously. But he observed. He noticed patterns. He saw that people living near swamps or stagnant water got sick more often. He made a leap, a really good leap.

It wasn’t magic or divine punishment. Maybe, just maybe, something real was happening. Something small. Something invisible.

It’s the kind of intuitive science that modern thinkers dream about. A mental leap from observation to hypothesis without any of the tools we’d normally consider essential. No lab coat. No petri dish. Just a curious Roman with a sharp mind and a deep mistrust of wetlands.

What’s fascinating is that Varro had access to centuries of Roman and Greek medical knowledge. The Greeks had their own theories about disease, mostly centered around the four humors (blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile). The idea was that illness resulted from imbalances in these bodily fluids. It was elegant, it made a certain kind of sense, and it was completely wrong.

Varro could have just repeated this accepted wisdom. Instead, he looked at actual evidence. Soldiers stationed near marshes died at higher rates. Farmers who drained wetlands reported fewer illnesses. Animals seemed healthier when kept away from stagnant water. From these observations, he theorized something was living in these environments and making people sick.

The revolutionary part wasn’t just that he proposed invisible organisms. It’s that he proposed a mechanistic, naturalistic explanation for disease at a time when most people still believed illness was punishment from the gods or the result of personal moral failings.

The World Wasn’t Ready for Varro

You’d think this idea would’ve caught fire. That someone, somewhere, would’ve picked it up and said, “Hey, maybe we should look into this.”

Nope.

Instead, the world doubled down on miasma theory, the idea that “bad air” caused disease, like some evil fog rolling through town. That stuck for, oh, 1,800 more years.

Why? Because germs were invisible. And people like their threats visible. Angry gods? Easy to conceptualize. Demons? Spooky but familiar. But tiny bugs you can’t see living in your mouth? Too weird. Too unsettling.

There’s also the problem of proof. Varro couldn’t show anyone these creatures. He couldn’t put them under a lens or grow them in a culture. His theory, however accurate, was just that: a theory. And theories without evidence don’t tend to overturn established medical doctrine, especially when that doctrine has the weight of centuries behind it.

The Greek physician Galen, who lived about 200 years after Varro, became the dominant medical authority for over a millennium. Galen’s work was brilliant in many ways, he advanced anatomy and physiology significantly, but he didn’t embrace Varro’s idea about invisible disease-causing organisms. Instead, Galen promoted miasma theory and the humoral system. Since Galen’s works were translated, copied, and taught throughout the medieval period in both Europe and the Islamic world, his ideas became medical gospel.

Varro’s farming manual, meanwhile, was read primarily by agricultural types interested in crop rotation and livestock management. The revolutionary medical insight buried in its pages went largely unnoticed by physicians and natural philosophers.

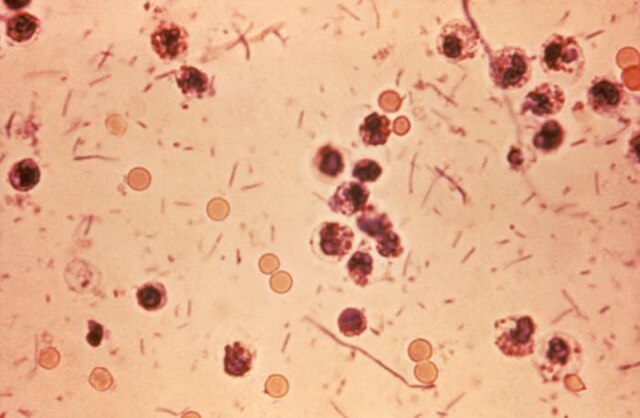

It wasn’t until the 17th century, when the microscope was invented, that people even saw microorganisms. Dutch scientist Antonie van Leeuwenhoek peered through his handcrafted lenses in the 1670s and became the first person to observe bacteria and protozoa. He called them “animalcules,” little animals, and was absolutely astonished by what he found.

But even then, it took another 200 years before doctors started washing their hands regularly. Hungarian physician Ignaz Semmelweis noticed in the 1840s that doctors who washed their hands between performing autopsies and delivering babies had dramatically lower rates of maternal mortality. His reward? Being mocked by the medical establishment, losing his job, and eventually dying in an asylum. The medical community didn’t widely accept hand-washing until after Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch proved germ theory in the 1860s-1880s.

Varro was right. We were just really, really late to the party.

What Rome Actually Believed About Disease

To appreciate how radical Varro’s idea was, you need to understand what everyone else thought at the time.

Most Romans believed disease had multiple causes. Divine displeasure was a big one. If you offended the gods, they might strike you with illness. This is why temples to healing deities like Asclepius were so popular, people went there to make offerings and pray for recovery.

There was also the concept of contagion, but not in the scientific sense we understand today. Romans knew that some diseases seemed to spread from person to person. The historian Thucydides had described the plague of Athens in 430 BCE, noting how the disease passed between people. But the mechanism was mysterious. Was it a curse that spread? Evil spirits? Bad luck?

The miasma theory, which Varro’s contemporaries favored, held that rotting organic matter released poisonous vapors into the air. Breathe in these noxious fumes and you’d get sick. This is why the word “malaria” literally means “bad air” in Italian. The disease was associated with swampy regions, but the Romans thought the swamp itself produced toxic air, not that mosquitoes breeding in the water carried parasites.

Varro’s leap to invisible living organisms was completely outside this framework. He wasn’t talking about vapors or humors or divine punishment. He was proposing that life existed below the threshold of human vision and that this unseen life could cause harm. In an age when the smallest thing most people had seen was probably a flea, this required an extraordinary imagination.

A Guy Ahead of His Time (and Maybe Ours)

In a way, Varro feels kind of familiar. You know that one friend who says something slightly bonkers at dinner, like “aliens are real” or “AI will eventually write poetry better than humans” and ten years later, they’re suddenly a prophet?

That’s Varro. Except swap the dinner party for a Roman villa and the aliens for bacteria.

He’s a reminder that sometimes, the smartest people aren’t the loudest. And that really good ideas don’t always win, at least not right away.

There’s something almost poignant about Varro’s legacy. He wrote over 600 works. Of those, only two survive in complete form: the De Re Rustica and De Lingua Latina, a work on Latin grammar. Everything else, his writings on history, philosophy, law, all the accumulated wisdom of one of Rome’s greatest scholars, is lost. We know they existed only because other writers referenced them.

Imagine if one of those lost works expanded on his germ theory. What if he’d written an entire medical treatise exploring the idea of invisible organisms causing disease? Would it have made a difference? Would anyone have listened?

We’ll never know. But what we do know is that Varro represents a kind of intellectual courage that’s always been rare. The willingness to look at accepted explanations and say, “I don’t think that’s quite right. What if there’s something we’re missing?”

Modern Recognition (Finally)

Today, historians of science recognize Varro’s contribution, though he’s still not a household name like Pasteur or Koch. Medical historians point to his passage in De Re Rustica as one of the earliest anticipations of germ theory in Western literature.

There’s debate about whether Varro should get credit for “discovering” germ theory. After all, he couldn’t prove his hypothesis, and his idea didn’t lead directly to any advances in medicine. Some argue that scientific credit should only go to those who can demonstrate and verify their theories.

But that feels overly harsh. Varro did something remarkable. With no instruments, no experimental method, no scientific community to support his inquiry, he looked at the world and intuited something fundamentally true about how disease works. That deserves recognition, even if he couldn’t build a complete theory around it.

It’s worth noting that other cultures had similar insights. Ancient Indian texts mention the idea of invisible creatures causing disease. Chinese medicine had concepts of external pathogens. But Varro’s formulation is striking for its specificity and for how closely it aligns with modern understanding.

What Varro Teaches Us About Innovation

The story of Marcus Varro isn’t just about one man being right before his time. It’s about how innovation actually works, which is often messier and more random than we’d like to think.

Good ideas don’t always come from the expected places. Varro’s insight appeared in a farming manual, not a medical treatise. Sometimes the outsider perspective is the one that sees things most clearly precisely because they’re not locked into disciplinary assumptions.

Timing matters enormously. An idea introduced before the culture, technology, or intellectual framework exists to support it will likely disappear, no matter how correct it is. Varro needed microscopes to exist. He needed a scientific method for testing hypotheses. He needed a medical community ready to question fundamental assumptions. None of that existed in 36 BCE.

And perhaps most importantly, being right isn’t enough. You need to be right in a way that others can verify, in a language they can understand, at a time when they’re ready to listen. Varro had the insight but not the tools or the audience.

Final Thoughts: The Wisdom Buried in Footnotes

It’s kind of poetic that Varro’s germ theory shows up not in a scientific manifesto, but in a casual aside in a farming guide. Like he was just tossing off brilliance between crop rotations.

But that’s what makes it stick with you. Because if someone could see that clearly, that early, what else have we overlooked?

How many other insights are buried in old texts, dismissed as speculation or metaphor? How many times has someone been right about something important and simply been too far ahead of their contemporaries to be heard?

Varro may not have gotten his moment back then. But maybe now, 2,000 years later, we can finally say: Marcus, you called it.

And we owe you one.

More than that, we owe it to ourselves to stay curious, to question accepted wisdom, and to remember that sometimes the wildest ideas turn out to be the truest ones. Just because you can’t see something doesn’t mean it isn’t there. Varro understood that. It only took the rest of us two millennia to catch up.

So the next time you wash your hands, maybe spare a thought for the Roman farmer-scholar-warrior-polymath who looked at a swamp and saw invisible killers. He deserved better than footnotes. But at least now, he’s getting his due.

Sources:

1. Harvard University’s Loeb Classical Library – De Re Rustica

2. The Atlantic – The Roman Who Predicted Germ Theory

3. National Institutes of Health – Early Theories of Disease Causation