General Hitoshi Imamura once walked with the quiet authority of an old-school soldier. A career military man in the Imperial Japanese Army, he carried himself with a code, a kind of harsh, uncompromising honor rooted in loyalty to the Emperor and duty to Japan. For decades, that code guided his rise through the ranks. But in the end, it couldn’t save him from what he’d become.

This is the story of how a decorated general became a war criminal. And how even honor can become a weapon when it’s disconnected from humanity.

The Making of a Military Man

Hitoshi Imamura was born in 1886 in Miyagi Prefecture, the son of a military officer. In Meiji-era Japan, the military was transforming from a feudal samurai tradition into a modern fighting force modeled on Western armies. Young men like Imamura were raised on stories of samurai loyalty and sacrifice, but trained in contemporary warfare tactics.

He entered the Imperial Japanese Army Academy in 1903, graduating near the top of his class. This wasn’t just military school. It was indoctrination into a worldview where individual life meant nothing compared to service to the Emperor. Students learned that death in battle was the highest honor, that surrender was unthinkable shame, and that Japan had a divine destiny to lead Asia.

Imamura absorbed these lessons completely. He was a model officer: disciplined, strategic, and utterly dedicated. He served in multiple campaigns, steadily rising through the ranks. By the 1930s, as Japan’s military began its aggressive expansion across Asia, Imamura was a respected colonel with a reputation for competence and old-fashioned military virtue.

The Code That Defined Him

What set Imamura apart from many of his peers was his adherence to what he saw as proper military conduct. In an army increasingly dominated by young, radical officers who advocated total war and brutal tactics, Imamura represented an older tradition. He believed in clear rules of engagement, proper treatment of subordinates, and maintaining discipline.

Those who knew him described him as thoughtful, even respectful, at least by the standards of Japan’s militarized elite. He wasn’t one of the screaming, sword-waving fanatics who terrorized their own troops as much as the enemy. He was calm, methodical, professional.

But here’s the thing about codes of honor: they can blind you to what’s actually happening around you. Imamura’s sense of duty was so absolute that it left no room for questioning the mission itself.

From Officer to Empire Builder

By 1941, when Japan launched its coordinated attacks across the Pacific, Imamura was a lieutenant general commanding the 16th Army. His mission was to conquer the Dutch East Indies, the resource-rich Indonesian archipelago that supplied oil, rubber, and other materials Japan desperately needed for its war machine.

The invasion began in January 1942. Imamura’s troops moved with shocking speed and efficiency. They took Java, Sumatra, Borneo, and other islands in a matter of weeks. The Dutch colonial forces, already weakened and demoralized, crumbled. By March, Imamura was military governor of Java, controlling territory with a population of over 60 million people.

He knew how to win battles. And he believed in the mission: a “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere” where Japan would liberate Asia from Western colonialism and create a new order with Tokyo at the center. It was propaganda, of course, but Imamura seemed to genuinely believe it. In his mind, he wasn’t conquering. He was liberating.

The Governor Who Tried to Be Different

As military governor, Imamura made some unusual choices. He ordered his troops to respect Indonesian culture and religion. He released Indonesian nationalist leaders from Dutch prisons, hoping to win local support. He even allowed limited self-governance in some areas.

Compared to other Japanese-occupied territories, Java under Imamura was slightly less brutal. Slightly. He genuinely seemed to believe that if Japan treated the Indonesians well, they would embrace Japanese leadership. It was a pragmatic approach, but also naive. Because conquest is conquest, no matter how politely you do it.

And beneath Imamura’s relatively moderate policies, the occupation was still an occupation. Resources were extracted to feed Japan’s war effort. Labor was forced. Dissent was crushed. And the military culture that Imamura was part of, the culture that saw non-Japanese as inherently inferior, infected everything his administration did.

Behind the Curtain: Atrocities Under His Command

Here’s where things get grim, where the gap between Imamura’s self-image and reality becomes impossible to ignore.

Under Imamura’s command, Japanese troops were implicated in mass executions, forced labor, systematic torture, and deliberate starvation, particularly in prisoner-of-war camps across Indonesia. While Imamura reportedly tried to instill discipline and maintain standards, the sheer scale of the atrocities suggests something deeper than just a few bad subordinates acting on their own.

Either he didn’t know what was happening, which would make him criminally negligent, or he knew and allowed it to continue, which would make him directly complicit. The truth was probably somewhere in between: he knew some of it, turned a blind eye to other parts, and convinced himself that harsh measures were necessary for military efficiency.

The POW Camps

The treatment of prisoners under Japanese control during World War II was systematic brutality. In camps across the territories Imamura controlled, Allied POWs and civilian internees faced starvation rations, medical neglect, random beatings, and execution for minor infractions.

Japanese military doctrine considered surrender the ultimate disgrace. Soldiers were expected to fight to the death or commit suicide rather than be captured. This meant that POWs, who had surrendered, were viewed with contempt as men who had forfeited their right to be treated as human beings.

Imamura was aware of conditions in the camps. He received reports. He made inspections. But he didn’t fundamentally change the system. The camps remained death traps where men slowly starved or died of preventable diseases while performing forced labor.

The Death Railway and Forced Labor

In one notorious case, the Burma Railway, also known as the Death Railway, cost the lives of over 100,000 laborers and POWs who were worked to death building a supply route through impossible jungle terrain. Though Imamura wasn’t directly in charge of the railway project, he was part of the command structure that approved and enabled it.

The culture of brutality and dehumanization was widespread across Japanese-occupied territories. Guards who showed mercy were often punished themselves. Officers who questioned orders were removed. The system rewarded cruelty and punished compassion.

And Imamura, as a senior commander overseeing millions of people across multiple territories, was part of that system. His hands might not have wielded the clubs or ordered specific executions, but his signature was on the policies that made them possible.

The War Ends: Reckoning in Rabaul

In late 1942, Imamura was transferred to Rabaul in New Britain, where he became commander of the 8th Area Army, controlling Japanese forces across the South Pacific. It was supposed to be a promotion, but it became a trap.

Allied forces isolated Rabaul, cutting it off from resupply. Imamura and over 100,000 Japanese troops were left stranded, unable to retreat or advance. For three years, they sat in what became an open-air prison, watching the war pass them by.

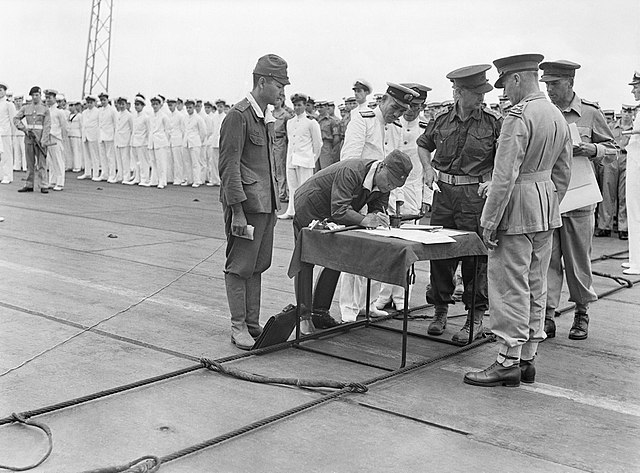

When Japan surrendered in August 1945, Imamura was still in Rabaul. He formally surrendered his forces to Australian commanders. Unlike some Japanese officers who committed suicide rather than face the shame of defeat, Imamura chose to live. Perhaps he already sensed what was coming.

The Tribunal

After Japan’s surrender, Imamura was tried by an Australian military tribunal in 1947. The charges were extensive: responsibility for the mistreatment and deaths of POWs, forced labor, executions of civilians, and failure to maintain proper control over troops under his command.

The evidence was damning. Survivors testified about conditions in camps. Documents showed that Imamura had received reports about abuses and done little to stop them. The prosecution argued that as commander, he bore ultimate responsibility for everything that happened in territories under his control.

Imamura didn’t deny the facts. He acknowledged that terrible things had happened. But he struggled to accept personal responsibility. In his mind, he had tried to be a good commander, tried to maintain discipline and order. How could he be blamed for subordinates who disobeyed his intentions?

The tribunal wasn’t interested in his intentions. They sentenced him to life in prison.

A Sentence That Spoke Volumes

But here’s what made headlines and what still puzzles historians: Imamura voluntarily requested solitary confinement.

Yes. Solitary. By choice.

He said he deserved to reflect in isolation on the horrors committed under his leadership. While other convicted war criminals were held in communal prison settings, Imamura asked to be alone. For nearly six years, he lived in a small cell at Sugamo Prison in Tokyo, by his own request.

What Was He Thinking?

Was it genuine remorse? An attempt at redemption through suffering? Or was it something more complex, a final expression of that rigid code of honor that had defined his life?

In traditional samurai ethics, failure brings shame that can only be addressed through sincere reflection or ritual suicide. Imamura had chosen not to commit suicide, so perhaps the solitary confinement was his way of performing penance while still living.

He spent his time in isolation reading, meditating, and reportedly writing poetry. He refused most visitors. He asked for nothing beyond basic necessities. Prison officials said he was a model inmate, quiet and causing no trouble, alone with his thoughts and his conscience.

Some saw it as noble. Others saw it as theater, a performance of contrition designed to rehabilitate his image. The truth is probably that Imamura himself didn’t fully understand his own motivations. Guilt, pride, shame, and a lifetime of military discipline all mixed together in ways even he couldn’t untangle.

Early Release and the Question of Justice

General Imamura was released in 1954, just seven years after his life sentence began. Why so early? Cold War politics played a role. As tensions rose between the West and communist China and the Soviet Union, the United States wanted Japan as an ally. War crime prosecutions became inconvenient reminders of past enmity.

Many convicted war criminals were released early as part of a broader political calculation. The message to survivors and victims was clear: your suffering matters less than current geopolitical needs.

Imamura returned to civilian life in Japan. He lived quietly, avoiding publicity. Unlike some other war criminals who sought to justify their actions or rebuild their reputations, Imamura remained largely silent. He didn’t write memoirs. He didn’t give interviews. He didn’t seek forgiveness from the public.

He died in 1962 at age 76, largely forgotten outside of academic circles. No state funeral. No military honors. Just a quiet end to a complicated life.

Legacy: Complicated, Controversial, and Cautionary

Unlike other infamous war criminals, Imamura didn’t crave attention. He didn’t try to rewrite history or claim he was just following orders. He just faded into obscurity, leaving behind questions rather than answers.

But the shadow of what happened under his watch still lingers, particularly in Indonesia and among the families of POWs who suffered in his camps.

The Uncomfortable Questions

It forces us to ask uncomfortable questions: How much responsibility does a leader bear for the actions of their subordinates? Can honor coexist with silence in the face of suffering? Is repentance real if history forgets it?

If a general tries to maintain some standards but operates within a system of brutality, does that make him better than his peers or just as guilty? Is choosing solitary confinement meaningful atonement or just symbolic gesture?

There are no easy answers. Imamura exists in a moral gray zone that makes people uncomfortable. We want our heroes and villains clearly defined. He was neither and both.

What the Survivors Said

For many survivors of Japanese POW camps, Imamura’s relative moderation meant nothing. They had watched friends die of starvation and disease. They bore the scars of beatings and torture. Whether the commander who enabled their suffering was personally polite or believed in military honor was irrelevant to them.

Some survivors testified that conditions were slightly better in areas under Imamura’s direct control compared to other Japanese-occupied regions. But “slightly better than the worst atrocities” is not exoneration. It’s just a different degree of horror.

Final Thought: The Uniform Never Tells the Whole Story

Imamura’s fall wasn’t dramatic. It was quiet. Introspective. Almost anti-climactic. But maybe that’s what makes it so haunting.

There was no fiery end, no last stand, no courtroom theatrics where he defiantly defended his actions. Just a man alone in a cell he’d chosen, replaying the choices that destroyed countless lives, trying to reconcile the soldier he thought he was with the war criminal he’d become.

We often want our villains cartoonish and easy to hate. Imamura wasn’t that. He was something more unsettling: a man who believed in duty above all, until that very sense of duty became the excuse for enabling inhumanity.

He thought he was better than the worst officers in the Imperial Japanese Army. And maybe he was, marginally. But being better than the worst still left him complicit in some of the 20th century’s gravest crimes.

The Danger of Blind Obedience

Sometimes, the most dangerous people are the ones who think they’re doing the right thing. Imamura never saw himself as evil. He saw himself as a loyal soldier serving his country. That self-image allowed him to overlook or rationalize horrors that should have been unacceptable to any decent person.

His story is a warning about the dangers of codes that value obedience over conscience, loyalty over humanity, and duty over moral judgment. It’s a reminder that good intentions and personal honor mean nothing if they don’t translate into actually preventing harm.

Hitoshi Imamura lived and died with his code intact. But that code, for all its talk of honor and discipline, couldn’t answer the most important question: were you a good man?

The prisoners who starved in his camps, the laborers who died building his railways, and the families who never got their loved ones back would probably say no.

And that judgment, more than any tribunal’s sentence, is the one that history will remember.

Sources:

1. National WWII Museum: Japanese War Crimes Trials

2. Yamamoto, Masahiro. Nanking: Anatomy of an Atrocity. Praeger Security International, 2000.

3. Australian War Memorial: War Crimes Tribunal Records