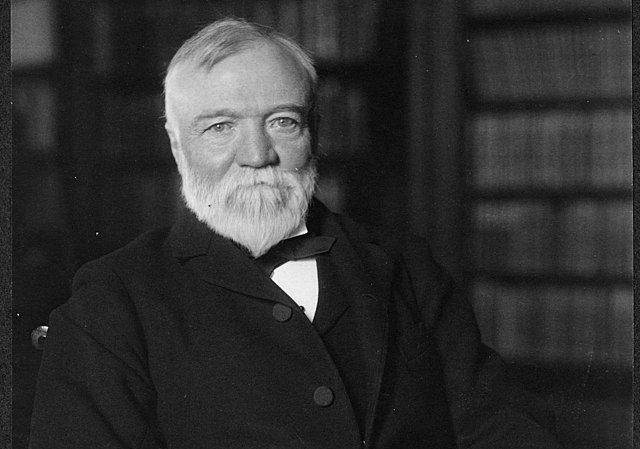

Andrew Carnegie: The Billionaire Who Died Broke (on Purpose)

Imagine amassing a fortune so massive it could rival nations, only to give nearly all of it away. That’s exactly what Andrew Carnegie did. And not out of guilt or PR spin, but because he truly believed money should serve humanity, not its owner.

Rags to Riches, for Real

Carnegie wasn’t born into wealth. In fact, his early life reads more like a Dickens novel than a CEO profile. He was born in 1835 in a one-room cottage in Dunfermline, Scotland. His family was so poor they shared a single bed. His father was a handloom weaver whose livelihood was destroyed by the rise of industrial textile mills. When the work dried up completely, the family faced a choice: stay and starve, or gamble everything on America.

When Carnegie was 13, they emigrated to the United States in search of a better life, borrowing money for passage and arriving in Allegheny, Pennsylvania (now part of Pittsburgh) with almost nothing. Carnegie started working immediately as a bobbin boy in a cotton factory, changing spools of thread for 12 hours a day. He made $1.20 a week.

That’s not a typo. Adjusted for inflation, that’s barely $40 in today’s money. For 72 hours of work. He was a child laborer in every sense of the term.

But Carnegie was ambitious and brilliant. He taught himself to read and write better by borrowing books from a local benefactor who opened his personal library to working boys every Saturday. This experience would profoundly shape Carnegie’s later philanthropy. He never forgot what access to books meant to a poor kid with nowhere else to turn.

Through a mix of brainpower, relentless networking, and good timing, he worked his way up. He became a telegraph operator, memorizing Pittsburgh’s business landscape by reading the messages he transmitted. Then he caught the attention of Thomas Scott, a railroad executive who hired him as a personal assistant. Carnegie learned everything: how railroads worked, how to invest, how to read markets, how power actually operated.

He started investing his tiny savings in railroad sleeping cars, oil, and iron. Every investment multiplied. By his late twenties, Carnegie was making more from investments than from his salary. He saw the future: steel. America was building railroads, bridges, and skyscrapers. They all needed steel.

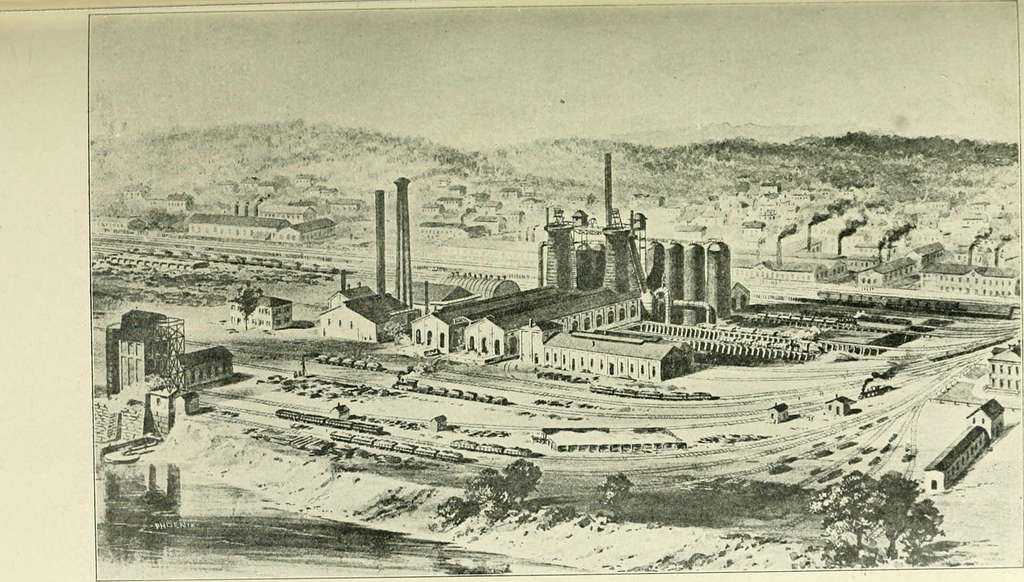

Eventually, he built Carnegie Steel, which became the largest and most profitable steel company in the world. He revolutionized the industry with the Bessemer process, vertical integration, and ruthless cost-cutting. By 1901, his company produced more steel than all of Britain.

That year, he sold Carnegie Steel to J.P. Morgan for $480 million (about $17 billion today, though some estimates put the equivalent even higher). Morgan merged it with other companies to create U.S. Steel, the first billion-dollar corporation.

Carnegie was 66 years old and one of the richest men alive. And then he started giving it all away.

Giving It All Back

By the time he died in 1919, Carnegie had donated over 90% of his fortune, approximately $350 million, equivalent to roughly $5 billion today. Schools. Libraries. Museums. Scientific research. Concert halls. Peace initiatives. He believed in lifting people up through education and culture, not just handing them cash.

His famous line, from his 1889 essay “The Gospel of Wealth,” put it bluntly: “The man who dies rich, dies disgraced.”

Carnegie argued that wealthy individuals had a moral obligation to redistribute their fortunes during their lifetimes. Not through inheritance, which he thought bred lazy, entitled children. Not through random charity, which he considered inefficient. But through systematic philanthropy that gave people tools to improve themselves.

He funded over 2,500 libraries across the English-speaking world. Walk into almost any town in America, Britain, Canada, Australia, or New Zealand, and if there’s a beautiful old library building with Carnegie’s name carved into it, he probably paid for it. The catch? The town had to provide the land and promise to maintain it. Carnegie wouldn’t enable laziness. Communities had to invest too.

He helped establish Carnegie Mellon University, originally Carnegie Technical Schools, to provide education to working-class students. His money founded the Carnegie Institution for Science, which funded groundbreaking research. The Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching created the first pension system for university professors. Carnegie Hall in New York became one of the world’s premier concert venues.

He built the Peace Palace in The Hague. He established the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. He funded thousands of church organs because he believed music elevated the human spirit. He created the Carnegie Hero Fund to recognize ordinary people who risked their lives saving others.

To him, wealth came with moral responsibility. You could enjoy it, sure. But you had an obligation to reinvest it into society, to create opportunities for others to rise as he had risen.

Why He Matters Today

We live in a world where billionaires buy social media platforms, mega-yachts longer than football fields, and sometimes, entire political systems. We live in an era where the wealth gap keeps widening, where a handful of individuals control more resources than entire nations.

But Carnegie? He built concert halls and universities. He built 2,500 libraries.

He didn’t want a statue or a legacy of monuments to his ego. He wanted a smarter, more educated, more curious world. He wanted the next poor Scottish immigrant kid to have access to books without needing a personal benefactor.

This wasn’t about charity in the warm-and-fuzzy sense. Carnegie was strategic and, honestly, a bit controlling about it. He thought the best way to help people wasn’t just giving them fish or even teaching them to fish. It was building the damn fishing school, stocking it with the best equipment, and then letting people prove themselves.

Give them tools. Give them access. Give them knowledge. Then let them grow. That was his philosophy, articulated in “The Gospel of Wealth”, an essay that remains influential in philanthropic circles today.

Not a Saint, But Still Inspiring

Was he perfect? Absolutely not. He was a ruthless capitalist before he became a philanthropic icon. His workers weren’t exactly living their best lives. They worked 12-hour shifts, six or seven days a week, in dangerous conditions. Carnegie preached libraries and education while his employees couldn’t afford books or time to read them.

The infamous Homestead Strike of 1892 permanently stained his legacy. Workers at his Homestead Steel Works in Pennsylvania, protesting wage cuts and terrible conditions, were met with violence. Carnegie’s business partner, Henry Clay Frick, hired Pinkerton detectives, essentially private mercenaries, to break the strike. The resulting battle left at least ten people dead and dozens wounded.

Carnegie was in Scotland at the time, conveniently absent while his company waged war on his workers. He publicly supported workers’ rights to organize, but when his own profits were threatened, he let Frick handle it with guns. The hypocrisy was stark and his reputation never fully recovered.

But here’s the twist: he saw the flaws, eventually. He wrestled with them publicly. His later writings acknowledged that the industrial system created terrible inequality. He knew he’d made his fortune on the backs of workers he paid poorly. And in the end, he chose to use that fortune not to entrench dynastic power or build monuments to himself, but to dismantle barriers for future generations.

That kind of evolution matters. It doesn’t erase the harm, but it suggests something about the possibility of moral growth, about the capacity for wealthy, powerful people to actually change course rather than just protect their interests until death.

What Would Carnegie Do?

Carnegie’s story isn’t just history. It’s a mirror held up to our current moment. What are we doing with what we have? Whether it’s time, talent, or money, are we hoarding it? Using it to signal status? Or deploying it to lift others?

Modern billionaire philanthropy often cites Carnegie as inspiration. Bill Gates and Warren Buffett’s Giving Pledge, where billionaires commit to giving away most of their wealth, echoes Carnegie’s philosophy. But there are crucial differences. Carnegie gave while he was alive, maintaining control and ensuring his vision was implemented. He believed dead people’s money often got wasted by bureaucrats and heirs.

Some modern critics argue Carnegie-style philanthropy is fundamentally flawed. It allows wealthy individuals to shape society according to their personal vision, bypassing democratic processes. Why should one person decide what a community needs? Shouldn’t workers have been paid fairly in the first place, rather than waiting for Carnegie to feel generous later?

These are valid questions. But they don’t erase what Carnegie actually accomplished or the sincerity of his belief that wealth was a public trust.

He died in 1919 with about $30 million left, which he’d failed to give away before his death (he tried, but ran out of time). That amount, adjusted for inflation, would be substantial today but nowhere near his peak wealth. He’d given away roughly 90% of everything he’d ever earned.

But his real legacy isn’t measured in the money he kept or gave. It’s sitting on the shelves of a Carnegie library in a small town in Kansas. It’s in a classroom at Carnegie Mellon where a first-generation student is studying engineering. It’s in research funded by the Carnegie Institution that expanded human knowledge. It’s in the idea that money is a tool for building better futures, not a throne to sit on until you die.

That idea feels radical now. Maybe it always was. But Andrew Carnegie, robber baron turned philanthropist, child laborer turned billionaire, ruthless businessman turned generous benefactor, proved it was possible to actually mean it when you say wealth should serve humanity.

The question is: who’s willing to follow his example today?

Source:

1. Carnegie Mellon University – History

2. History.com – Andrew Carnegie

3. Nasaw, David. Andrew Carnegie. Penguin Books, 2007.